Policy Papers and Reports

/ Israel and the East Mediterranean

Policy Papers and Reports

/ Israel and the East Mediterranean

Winds of change have begun blowing across the Middle East in early 2011. For the first time in decades, Arab citizens in different countries have been going to the streets and demanding freedom and basic human rights. In much of Europe and North America, these developments have been by and large greeted with enthusiasm and hope for democratization in the Middle East. Israel, however, has been viewing things differently. It has been examining the new regional situation with considerable concern, and even fear. The Israeli consensus is that the country is witnessing the start of a long era of instability, with increased threats of regional radicalization and Islamism. The Israeli government, led by Benyamin Netanyahu, stresses that Israel should wait and see how developments in the Middle East progress, and should not take any major diplomatic initiatives until the region is stable once again.

But the potential threats form only part of a larger and more complex picture. As acknowledged by Israel’s President Shimon Peres, the Arab Spring also holds opportunities for Israel’s regional foreign policies and for its relations with the Arab/Muslim world. Such opportunities are often neglected in Israel, as they tend to be over-shadowed by the dominant discourse that focuses on potential security concerns. But among the opportunities that the Arab Spring did bring Israel, there seemed to also be an opportunity to mend relations with Turkey — relations that were significantly strained following the May 2010 flotilla incident. While many of the Arab Spring opportunities for Israel required some progress in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process for their fulfillment, this was not necessarily the case regarding Israel and Turkey. Although the lack of a peace process does negatively impact Israel-Turkey relations, the major crisis between them at the time was a bi-lateral one, and could have been solved through a mutual agreement.

The crisis between Israel and Turkey, however, did not begin with the flotilla incident. It has flared up in light of Israel’s operation Cast Lead in Gaza, which started in late December 2008. Operation Cast Lead was a turning point in Turkey-Israeli relations. It put a halt to Turkey’s intense mediation efforts between Israel and Syria, and led to strong Turkish condemnation of Israel’s policy in Gaza and its consequences. Erdoğan’s clash with Peres in the Davos Summit, in January 2009, and his walking off the Davos stage with anger symbolized the beginning of a new era of crisis. This was further fuelled by the public humiliation of the Turkish Ambassador to Israel by Israel’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Danny Ayalon, in January 2010, in an attempt to protest an anti-Israeli TV series that was aired in Turkey. It was in this context – of an Israeli siege on Gaza and of a highly visible Israel-Turkey crisis – that the flotilla incident took place.

It is thus clear that the Israel-Turkey crisis is not all about the flotilla. It already began before. However, once the flotilla incident happened, it overshadowed other pending issues between Israel and Turkey. Finding a formula that will enable the two countries to move beyond this incident became a prerequisite for any effort to restore normal bi-lateral ties between them and to move towards reconciliation. Not only at the official governmental level but also at the societal level. Early attempts at resolving the flotilla incident did not bear fruit. Israel’s Industry, Trade and Labor Minister Benyamin Ben-Eliezer met in late June 2010 with Turkey’s Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu to discuss ways of resolving the crisis between Israel and Turkey. This meeting, as well as other efforts held in the second half of 2010, did not lead to a breakthrough.

Things seemed to be stuck. But, 2011 brought a new opportunity for Israel and Turkey to mend their bi-lateral relations. The re-election of Erdoğan in the June 2011 Turkish general elections, coupled with the dramatic events of the Arab Spring, provided a new political and regional context in which the relations could be re-evaluated. This context contributed to Turkey and Israel, with US mediation, making progress towards drafting an agreement between them. However, this agreement was eventually rejected by Israel in August 2011 leading to the eruption of a new cycle of escalating tension between the two countries.

The aim of this article is to analyze the Israeli decision-making process and discourse regarding the crisis with Turkey in 2011. It will first examine the changing circumstances of 2011, including the impact of the Arab Spring and the different manners in which Israel and Turkey reacted to it. Afterwards, it will focus on the Israeli decision to reject the draft agreement with Turkey and on the different phases of the Israeli reaction to the new crisis with Turkey that followed. Finally, it will reflect on possible next phases in Israel-Turkey relations, and on conditions that may assist in providing yet another opportunity for making the two former allies less alienated.

An Opportunity for Reconciliation

During the first half of 2011, it was common to hear from Turkish and Israeli pundits that once the June 2011 elections in Turkey are over, Erdoğan may very well move towards mending relations with Israel. Despite the fact that Israel was not a major issue in the election campaign, this assessment was based on the assumption that upon being free from electoral considerations, Erdoğan would have more room and political will to manoeuver towards fixing the Israel-Turkey crisis. Indeed, following the elections and AKP’s landslide victory, there was an effort by both sides to create some better atmosphere between the countries.

A few days after the elections, the Turkish organization IHH announced that it would not take part in another planned flotilla to Gaza. This was apparently decided upon due to pressure from Turkish government officials, and was regarded in Jerusalem (together with Turkey’s assistance to Israel regarding the December 2010 Mt. Carmel fire), as an indication that Turkey was pursuing a more constructive approach towards Israel. Netanyahu responded with a letter to Erdoğan, which congratulated him on his elections victory, and which stressed that the Israeli government “will be happy to work with the new Turkish government on finding a resolution to all outstanding issues between our countries, in the hope of reestablishing our cooperation and renewing the spirit of friendship which has characterized the relations between our peoples for many generations.”

Even Israel’s Deputy Foreign Minister Ayalon took part in the efforts to express renewed warmth between the countries. Ayalon met in Jerusalem with a group of Turkish journalists that decided to visit Israel, and claimed that he actually did not intend on humiliating the Turkish Ambassador in early 2010. Ayalon told the Turkish journalists that “the incident [in which the Ambassador was seated in a low chair] was a joke that was blown out of proportion,” that he has sent a letter of apology to the Turkish Ambassador, and that the cancellation of the second flotilla is a good opportunity for Turkey and Israel to restore their relations. He also posed for a Turkish journalist while sitting in a lower chair than her. Ayalon, though, did not change his hawkish position regarding the flotilla incident. He still hoped that the flotilla incident would be shelved by Turkey. This was unrealistic.

In parallel to these public diplomacy acts, the US had publicly encouraged the governments of Turkey and of Israel to work closely together. Reports began to appear claiming that the US was also mediating secret negotiations between Israeli and Turkish representatives. For the US, having its two major allies in the region at odds with each other was a strategic hardship it was willing to put strenuous efforts to resolve.

It was not only the Turkish elections that enabled this attempt at Turkish-Israeli reconciliation. While the elections did provide a more favorable political context for the sides to get closer together, it was the Arab Spring that provided a more favorable regional context. Turkey’s pro-active decision to side with the protesters in the different Arab countries and its aim at playing a central role in assisting peaceful transformations was of importance in this regard. It led to the collapse of the alliance between Turkey and Assad’s Syria, which was a key factor in Turkey regional foreign policies in recent years and which brought Turkey closer to the region’s radicals, such as Hamas and Iran; it led to a significant improvement in the relations and coordination between Turkey and the US in light of their mutual interests in the changing region; and it enabled Turkey to try and position itself as part of a new regional alliance of moderate (albeit critical of Israel) countries that work to prove that Islam and democracy are compatible. Turkey had to re-evaluate its ties in the region.

Turkey and Israel seemed to have more joint regional interests than before. Both countries aspire for regional stability and security (albeit holding often diverging views on the means to achieve this). The events in Syria brought the regional instability to the borders of Israel and Turkey, with some incidents of cross-border spillover already taking place – the flow of Syrian refugees towards Turkey, and the attempt by Syrian protestors to cross the border into Israel in the Golan Heights. In such a period of change and uncertainty, Israel and Turkey – the democratic and pro-Western countries in the region – could have benefitted from coordination and dialogue mechanisms enabling a joint look at the changing region, much like Turkey-US relations evolved for the better during the Arab Spring.

The improvement in Turkey-US relations, and the increased coordination between their leaders, enabled the US to have more leverage on Turkey to push it towards reconciliation with Israel. Moreover, Turkey’s continued interest to assume a mediator role between Israel and the Palestinians, as expressed by Abdullah Gül, also gave Turkey a reason to improve ties with Israel. In order to be a mediator, Turkey has to have good relations with both sides and open communication channels to them. These were assets that Turkey had in the past, and that previously helped it bring Israelis and Arabs closer together.

For Israel, the Arab Spring brought new reasons for mending relations with Turkey. In light of a region in turmoil, of fear from further isolation and from rising radicalism, of concerns from possible implications of the Palestinian approach to the UN and from the Iranian nuclear project – Israel should have been more interested in having at least normal relations with Turkey. Turkey is a significant regional power, one of the only Muslim countries willing at all to engage with Israel, a source of stability, and a country that can have a moderating effect on some regional actors and can serve as a channel between Israel and the new regimes in the Arab world.

However, the first year of the Arab Spring did not lead Israel to try and get closer to Turkey. Israel and Turkey differed in the way they viewed the changes in the Arab world. In contrast to Turkey’s pro-active and supportive approach to the Arab Spring, Israel adopted a passive approach that was preoccupied with threats and concerns. Israelis looked around them and saw the regional status quo, which they have grown to know and to feel relatively at ease with, collapse. They saw Muslim parties and movements grow stronger. They saw the fall of Hosni Mubarak, a strategic ally of Israel. They also saw demonstrations in front of Israeli embassies in Egypt and Jordan. Israelis began to doubt whether the existing peace agreements would survive the regional changes. They also feared that the Assad regime might initiate an Israeli-Syrian escalation in order to divert attention from the domestic unrest in Syria.

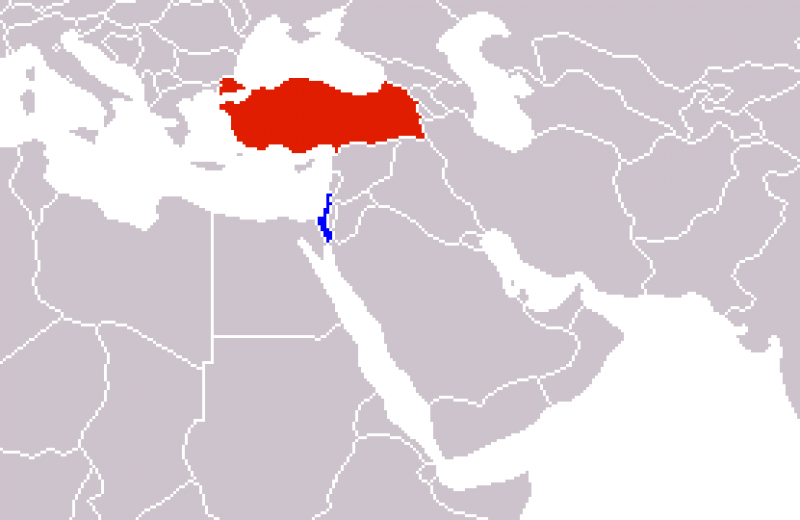

In light of this approach, the Israeli government decided to follow regional developments with a wait-and-see policy. It refrained from issuing statements of support to the Arab protesters and from calling on Arab leaders to step down. The Israeli government believed that until the region stabilizes – and even if this is to take several years – Israel should not initiate major diplomatic initiatives or take bold regional or pro-peace steps. By taking such an approach, Israel – unlike Turkey – gave up on the opportunity to play a role in the re-shaping of the region. It chose to try and dis-engage itself from Middle Eastern affairs and to seek new alliances in its periphery as a compensation for its lost regional alliances, including its relations with Turkey. Thus, Israel turned to develop increased cooperation with Cyprus, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria. Netanyahu’s visit to Cyprus in February 2012, the first-ever visit of an Israeli Prime Minister to the neighboring island, was a clear manifestation of this policy.

These official Israeli attitudes and policies were echoed in Israel’s public opinion. In February 2011, forty-six percent of the Israeli public thought that Egypt’s revolution will have a negative effect on Israel-Egypt relations (while only nine percent thought the opposite); seventy percent thought that the chance for democracy in Egypt in the foreseeable future was low; forty-six percent though that there were high chances for an Iranian-style Islamic regime forming in Egypt; and forty-eight percent thought that Egypt’s revolution will strengthen Hamas (while only thirteen percent thought the opposite). Attitudes did not change for the better as time went by. In November 2011, sixty-eight percent of Israelis believed that their country’s national security situation was worse than it was before the process of change in the Arab world started.

These negative beliefs regarding the Arab Spring were coupled with a belief that Turkey is aspiring for leadership in the changing Middle East and that it is bolstering its popularity in the Arab world through criticism of Israel. This combination had a negative impact on prospects for mending Israel-Turkey ties, and it overshadowed the above-mentioned joint interests that the two countries shared in light of the regional turmoil. Israelis were skeptic as to whether Turkey is at all willing to have better relations with Israel at this point in time.

The opportunity that emerged in 2011 for Israel-Turkey reconciliation was eventually left unfulfilled. The two countries held secret negotiations under US auspice, and senior representatives sent by both governments joined these talks. The aim was to agree on a formula, on an agreement, that would fix relations and that would lead to the shelving of the Palmer report. The Palmer Report was drafted by an UN-appointed committee that was supposed to assist in fixing the Israel-Turkey crisis. The report’s publication was postponed several times, in order to give the negotiators more leeway to try and reach an agreement.

With each delay, it became more apparent that the report – if and when published – would be used by both sides to reinforce a blame game between them. The report was gradually perceived as a verdict as to which side was guilty in the flotilla incident, rather than as a tool to promote a solution to the Israeli-Turkish crisis. Nevertheless, the fact that both sides came to realize that the report did not fully support their views became an incentive for progress in the negotiations. The report was to claim that Israel’s blockade of Gaza was legal – despite Turkey’s claims, while arguing that the IDF used unreasonable and excessive force in the takeover of the flotilla – despite Israel’s claims.

Eventually, the Israel-Turkey negotiations led to a draft agreement, which is said to have included an Israeli apology for operational mistakes that may have occurred during the takeover of the flotilla, Israeli compensation to the victims’ families, a restoration of full diplomatic ties between Israel and Turkey, and a guarantee by the Turkish government not to prosecute Israelis involved in the flotilla incident. Israel, however, decided to reject the agreement. In August 2011, following deliberations in the Israeli cabinet and despite US pressure, Netanyahu notified Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that Israel would not apologize to Turkey. Shortly afterwards, the Palmer report was leaked to the press, putting a halt to any attempts for reconciliation and leading to a renewed escalation of tensions between Israel and Turkey.

The draft reconciliation agreement that was rejected by Netanyahu, did in fact address Israel’s major concerns and interests – it included only a low-key and conditional version of an apology, it protected to a significant extent Israeli soldiers from law suits, it did not demand any change of Israeli policy regarding Gaza (as was demanded by Turkey before), and it ensured normal diplomatic ties between the countries. If so, why was such an agreement eventually rejected?

The Israeli Decision

In major Israeli state circles there was support for the reconciliation agreement. Israel’s Attorney General, Yehuda Weinstein, has reportedly advised Netanyahu to reach an understanding with Turkey, even if that meant issuing a general apology for operational mistakes and misuse of force in order to prevent lawsuits against Israeli soldiers. Within the defense establishment there was increased support for resolving the crisis even at the price of an apology to Ankara, as “Israel has a major stake in improving relations with Turkey in light of Turkey’s standing in the region, its past economic relationship with Israel, and the opportunity to renew defense-related export to Turkey.” Also, among Israel’s diplomatic circles there was support for such a move.

However, the voices within the bureaucracy and the establishment that supported an agreement with Turkey were usually not voiced in the public domain, and did not spark a public discourse on the issue. The negotiation process with Turkey was conducted behind closed doors, and the eventual Israeli decision was shaped by only a few political leaders, based on political considerations as well as their personal beliefs and ideology. There was no real public pressure on the issue, although the possible reaction of the public was definitely part of the political considerations that were actually taken into account.

Israelis did not understand the significance of the flotilla event for Turks. While Davutoğlu labeled the flotilla incident as “Turkey’s 9/11,” Israel dismissed the incident as an event used by Erdoğan to humiliate Israel and to improve Turkey’s standing in the Arab and Muslim world. Israelis were offended by the fact that Turkey did not stop the flotilla from sailing. They did not grasp the intensity of public emotions in Turkey regarding the killing of the Turkish citizens (which was seen in Israel as a legitimate act of self-defense) and that the demand for an apology was a consensual issue in Turkey, also shared by Israel’s friends there. Israeli officials wanted to believe that an expression of sorrow, without an apology, would be enough to satisfy Turkey. This was not the case. Moreover, Israelis were not aware of the nuances of the proposed agreement. The public debate focused on whether or not to apologize to Turkey, while there was very little understanding of what the agreement called Israel to actually apologize about, of the broader context in which such an apology will be made, and of what Israel was about to get in return.

The prevailing attitude in Israel was that relations with Turkey are doomed and that further deterioration is inevitable due to Erdoğan’s policies and statements, especially as the crisis between the countries began before the flotilla incident. Thus, an agreement was seen as being of no use, as Turkey would later come up with other demands (such as the lifting of the blockade of Gaza, a demand made already at the onset of the crisis) and with other sorts of criticism. Turkey, in turn, did not do enough to address the Israeli concerns and to help convince the Israeli public that should Israel take the needed actions to repair the relations, then these will actually bear fruit and will lead to the restoration of normal ties between the countries.

Israel’s Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman framed the debate about a possible Israeli apology around the issue of national pride. He claimed that national pride should be a guiding principle in Israel’s foreign policy making, and that an apology will undermine this pride and will thus weaken Israel’s strategic position in the region. This position was not shared by all members of the Israeli government. Minister Matan Vilani, who took part in the negotiations with Turkey, clearly stated that “whoever refers to the crisis with Turkey in terms of national pride does not understand the strategic reality in the Middle East”. Defense Minister Ehud Barak and Deputy Prime Minister Dan Meridor were also supportive of mending ties with Turkey. Netanyahu himself was reported to have already agreed on several instances to apologize to Turkey, before backing off due to domestic political reasons, namely the fear of criticism by major coalition partners or by key members of his government. It was the fierce objection by hard-liners Vice Prime Minister Moshe Ya’alon (who represented the government in the negotiations with Turkey) and Lieberman that eventually pushed Netanyahu to oppose the agreement, perhaps as an attempt not to alienate his right-wing constituency, in which Lieberman was enjoying increased popularity.

The Turkish response to the Israeli decision was extremely harsh. It was to serve as proof to those in Israel that opposed the reconciliation agreement that Turkey was in no way ready to once again actually become a friend of Israel. Erdoğan and his government, which promised in advance to sanction Israel should it refuse to take the actions Turkey has expected, embarked on a series of tough anti-Israeli statements and policies, In an interview to Al Jazeera, Erdoğan stated that the flotilla incident could have justified going to war if it was not for Turkey’s restraint. The Turkish Prime Minister announced a series of sanctions against Israel. Israeli diplomats were expelled and diplomatic relations were downgraded to second-secretary level, what has remained of the Israel-Turkey military cooperation was put on halt, official trade between the countries was frozen, Turkey tried to block Israel in multi-national institutions, Turkey announced that it plans to have a military presence in the eastern Mediterranean Sea to escort future flotillas and to challenge Israel’s natural gas drillings, that it will support lawsuits against Israeli soldiers, and that it will consider further sanctions. Erdoğan also declared that he is planning to challenge the Israeli blockade on Gaza by visiting the Gaza Strip in adjacent to a scheduled visit to Egypt. In a specific incident that was not included in the sanctions declared by Erdoğan, Israeli tourists were detained in the Istanbul airport, discouraging those Israelis who were still considering Turkey as a tourist destination. In early September 2011, not a day has passed without further escalation in the crisis. Turkey was trying to put a concrete, visible and high price tag on Israel’s decision to reject the reconciliation agreement. There was concern that things might get out of control.

The Israeli Discourse

The Israeli reaction to the crisis that has flared up with Turkey had several phases and aspects to it. The initial public response was one of confusion mixed with concern, even fear. Israelis could not understand Erdoğan’s conduct. The Turkish Prime Minister was portrayed in the Israeli media as an irrational, extremist and radical leader, who does not play according to international diplomatic norms. Erdoğan was occasionally compared to Israel’s worst enemies in the present and in the past, and was depicted as someone who is inherently against Israel and with whom cooperation or reconciliation are impossible. Israelis were amazed at what they saw as a disproportionate over-reaction. Some sought to explain it with frustration by Erdoğan over the legitimacy given by the Palmer Report to the Israeli blockade of Gaza. Questions started to pop up in the Israeli media about whether Turkey plans to carry out actual acts of warfare against Israel.

In light of the Turkish reaction, public opinion polls revealed a striking consensus within the Israeli public against any apology to Turkey. There were also public calls to boycott Turkish products, and to refrain from visiting the country. In the past, Turkey was a country that so many Israelis used to visit and towards which Israelis had such warm feelings. It was the only country in Israel’s neighborhood that embraced Israelis, and accepted them. Now it was seen in Israel as a country that changed course and that sided with Israel’s enemies. Israelis felt deeply betrayed by Turkey, claiming that it is Turkey that needs to apologize for enabling the IHH flotilla to set sail in the first place. While Turkey declared that its measures are directed against the current Israeli government and not against Israel or the Israeli public, this did not lead things to be seen more favorably in Israel. Reconciliation seemed far-fetched, with relations hitting rock-bottom.

In parallel, a different kind of Israeli discourse has begun to emerge. One that was critical of the Israeli government’s handling of the diplomatic crisis with Turkey, questioning Netanyahu’s decision to reject the reconciliation agreement, and stressing the importance of having good ties with Turkey. Traditional supporters of the relations with Turkey spoke up once again, and new voices – that were not heard prior to the Netanyahu’s decision about the agreement – came forth. These included political opposition figures, as Tzipi Livni and Tzachi Hanegbi from the Kadima party, but also public figures as the Governor of the Bank of Israel Stanley Fischer, and former-Minister Prof. Amnon Rubinstein.

This trend, which by-far did not represent the mainstream Israeli discourse, was somewhat empowered by some op-eds in the media, and especially by a column published by Nahum Barnea of Yediot Aharonoth, one of Israel’s most influential journalists. In September 2011, Barnea published an account of the secret negotiations between Israel and Turkey, publishing for the first time the actual content of the draft reconciliation agreement. His column made clear what was on the table and what Israel had missed out on. “Very few in Israel asked what Israel actually has to apologize about,” wrote Barnea, adding that “if you ask the Israeli on the street he will say confidently: Israel is asked to apologize on the IDF operation. This is not true”. According to the draft agreement, Israel had to apologize only for the very same operational mistakes that it already acknowledged through its self-appointment investigation committee.

The official Israeli policy towards Turkey in light of the heightened conflict was one of containment. Israeli government members kept quiet and did not retaliate towards Erdoğan’s statements and policies. The logic was to let Erdoğan play his game on his own, without reacting to his provocations. Israel believed that time will take its toll, and eventually Turkey would move on to other issues. Moreover, there was the expectation that the Barack Obama administration would help Israel in containing Erdoğan and in limiting his anti-Israeli rhetoric and actions. The Egyptian decision not to facilitate Erdoğan’s request to visit Gaza in September 2011 was perceived in the Israeli public as a direct outcome of American pressure.

The Israeli policy of keeping a low profile regarding the Turkish sanctions did not hold for all. It was Lieberman, in an attempt to make political gain among Israel’s right-wing constituency, who was reportedly planning an Israeli diplomatic retaliation against Turkey. Lieberman wanted to prove that it is Turkey who has much to lose from its policy towards Israel, and to portray himself as taking care of Israel’s national pride. It was leaked to the press that he was assessing different ideas on how to embarrass Turkey on the Armenian, Kurdish, and human rights issues.

However, the Netanyahu government opposed this initiative. The official Israeli discourse was trying to devalue the crisis with Turkey, and it was doing so by using two contradictory arguments. One argument held that Israel-Turkey relations had already deteriorated so much in recent years that they could not get much worse. The second was citing the fact that economic relations between the countries surprisingly reached a peak after the flotilla crisis, meaning that political tensions between the governments do not have an impact on the actual conduct of relations between the two societies.

What Can Happen Next?

The last couple of months of 2011 have brought more calm to Israel-Turkey relations. The regional focus has been redirected towards Syria, where Turkey has assumed a leading role against the Assad regime. Erdoğan’s “megaphone diplomacy” against Israel has been put to a relative halt, probably also due to American pressure. Moreover, there have been some renewed positive public diplomacy moves – Israel’s acknowledgement of a supportive Turkish role in the reaching Israel’s prisoners swap deal with Hamas, Israel’s offering of aid following the October 2011 earthquake in Van and Turkey’s willingness to accept it (that made the top news in Israel), and Netanyahu’s conversation with Erdoğan (for the first time in ten months) following the passing away of Erdoğan’s mother. Nevertheless, the January 2012 visit of Hamas’ Ismail Haniyeh to Turkey and the manner in which he was embraced by the Turkish leadership — reinforced the negative image that many in Israel currently hold towards Turkey’s policies.

In parallel to these political aspects, Turkey-Israel relations began to draw the attention of civil society organizations, which have been gradually trying to become involved in attempts to mend the relations. A growing number of think tanks, NGOs, and youth movements are seeking ways to bring together Israelis and Turks, something that was not sufficiently done even when the official relations between the countries were strong. In parallel, the US continues to express its support and desire for improving Israel-Turkey relations, with occasional media reports on discrete channels or on new bridging proposals.

These attempts at creating a better atmosphere, at establishing a new modus vivendi between the countries, and at preventing further deterioration are a positive step and should be encouraged. They will not be enough to normalize relations, but can help in defining what Israel-Turkey relations can look like given the current political and regional circumstances and in charting constructive paths to get there. By themselves, these efforts will not be able to dismantle the danger of further deterioration in the official relations. Events of near clashes, that used to take place in the Aegean as part of the Turkey-Greece dispute in the Aegean, might occur in the Mediterranean if things get worse. The reactivation of ties between the Israeli and Turkish air forces in December 2011 was an important step to try and prevent this from happening, especially as almost all official channels between the governments have been cut off. Israel and Turkey seem to be headed towards a period in which they will be engaged in fierce rivalry but within the context of some sort of diplomatic, economic, and social relations.

Normalization between Israel and Turkey can be likely in the event of a policy change in Israel regarding Turkey or of a breakthrough in the Arab-Israeli peace process. These do not seem feasible under the term of the current Israeli government, with Lieberman as Foreign Minister, but may become more plausible after the next Israeli elections, when a new coalition is formed. In the meantime, from the Israeli side, it is essential to educate the public and policy-makers that better ties with Turkey are both feasible and desirable, to maintain the existing level of economic and social ties, and to establish new channels for joint policy-dialogue between Israeli and Turkish scholars, policy analysts, and institutions.

Turkey-Israel relations have a long history of ups and downs. These were mostly linked to developments in Israeli-Arab relations, and not to bi-lateral crises resembling the flotilla incident. People tend to remember the Turkey-Israel “honeymoon” of the 1990s, but to forget the cold relations of the 1980s. As a new reality unfolds in the Middle East, with Turkey playing a central role in the re-shaping of Israel’s neighborhood, Israel and Turkey should strive to mend their bi-lateral relations. The 2011 opportunity for reconciliation was left unfulfilled, but the regional conditions that enabled this opportunity are still out there. It may not be long before another opportunity for reconciliation appears, due to a political change in Israel or to further regional realignments. Should this happen, Israel, Turkey, and their international allies should seize the opportunity and not let it sail past them, once again.