In the wake of the Palestinian UN campaign, many asked: ‘why?’ Why the sudden change in a decades-long process, why the abandonment of the bilateral process, why the confrontation on the international stage? Few, however, were asking ‘how?’ How was the process formed, how did this campaign gain momentum, how was it assessed in Ramallah? For the Palestinians, the UN campaign wasn’t so much a unique political anomaly as it was the resumption of a process they abandoned years ago in favor of bilateral negotiations. In the breakdown of viable negotiations in 2009 and 2010, resuming this process became the only realistic option. Their justification of this campaign, then, rested in the history they had at the UN with the international community.

If the Israeli government described the campaign as a unilateral act because it threatened the framework of Oslo, and the Palestinians described it as a multilateral act because it engaged multiple countries at the UN, then the truth was somewhere in between. In reality, it was a hybrid approach, a reconciliation of an emerging, holistic strategy growing within the Palestinian leadership that advocated internationalization. As a contingency plan, the UN campaign would form the spearhead of this internationalization track.

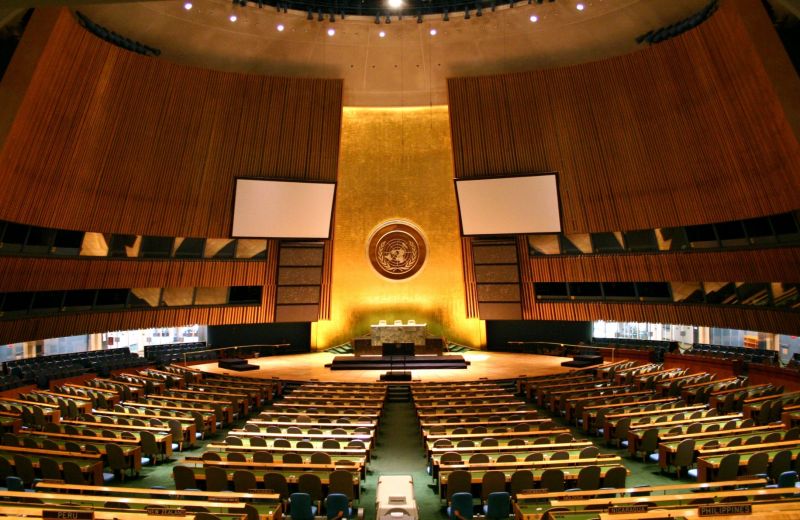

Palestinian leaders describe the UN campaign as only the most recent manifestation of an internationalization tactic that started in 1974 with the PLO’s ten-point plan, a manifesto designed to rally the resistance around a cause, but one that also acknowledged several political developments, leaving the PLO with maneuverability in the future. It was in 1974 that the PLO was first granted observer status at the UN, a process that evolved further in the 1980s, when the Lebanon—and later, Tunisia—based PLO leadership began modifying their positions regarding diplomacy and the realization of a Palestinian state alongside an Israeli state. This resulted in a heated debate in 1988 that divided the PLO: if the overall goal is a two-state solution, how best, then, to achieve this state? Within this debate two schools of thought emerged: those that argued in favor of going to the UN for recognition, and those that opposed. Those in favor argued the importance of gaining international recognition, of elevating the status of the PLO, of gaining legitimacy in representing the Palestinian cause. Those opposed raised several questions, namely what would become of the refugee issue and how would a liberation movement conform itself to the norms of the international community. By the time of the Palestinian declaration of independence at the end of 1988, the decision had been made in alignment with the latter, and the Palestinians compromised by applying as an entity to the UN in order to upgrade the PLO’s observer status.

Yet the history of the Palestinians at the UN shifts abruptly here. In the days following his address at the UNGA, Arafat finalized the overtures towards the US, renouncing terrorism at a teleconference. The US had the clearance it needed to begin a dialogue, and the Palestinian focus would shift from the internationalization track to the bilateral. In the coming years, the Palestinian delegation at the UN would tread water, resolutely avoiding antagonizing the US or Israel as bilateral negotiations became the primary focus for the next two decades.

Only in 2009, when faced with an undesirable status quo and an increasingly despondent populace, did the internationalization track reemerge. Confronted with a strategic dilemma, Abbas was forced to choose which track to pursue: reconciliation with Hamas, violent resistance, negotiations, or internationalization. With pressures from both within and without the Palestinian leadership, Abbas chose to prepare for the internationalization track, a convenient combination of a number of options that had the added advantage of fitting into the Palestinian historical narrative. As one official put it: “It’s as if the stopwatch we started in 1974 and paused in 1988 was resumed again in 2009.” In actuality, it was the only realistic policy option available.

That year, it was clear that the situation was dire for the Palestinians. In the wake of Cast Lead, Netanyahu’s resurgence, settlement moratoriums, international reports, an increasingly bitter Fatah-Hamas split, and threats of resignation—Abbas responded by consolidating the national agenda and setting the political course towards internationalization. In the eyes of the Palestinian leadership, there are tracks that complement each other, and tracks that do not. The UN campaign and bilateral negotiations work together; violent resistance and negotiations do not. In choosing the internationalization option, Abbas was reorienting towards one of the last remaining areas of Palestinian diplomatic strength: the UN.

Soon after, Abbas ordered his government to begin laying the foundations for the shift to the internationalization track. This shift would include incorporating several tactics into one new, hybrid tactic, with the UN campaign as the spearhead. The contingency plans, the list of UN-affiliated organizations, the procedural outline—all were developed to lay the technical foundation in case a political decision was made. A year later, in 2010, that political decision had been made, and a theoretical possibility became a practical reality.

In the breakdown in talks with Israel in late 2010, one Palestinian official described the situation as: “clear that the bilateral was, at best, closed off for the time being, and at worst, dead.” The Israelis and Palestinians had reached an impasse, and Abbas went to the Arab League meeting in Sirte, Libya to announce his tactical shift. The League backed his decision to abandon talks, and in the coming months the Palestinians began revealing the details of the newest manifestation of the UN campaign. 2011 saw a period of intense pressure from the US and Israel towards the Palestinians, with all sides blaming the other for the current stalemate.

Opinions vary regarding Abbas’s attitude toward the UN campaign that year. In interviews, officials describe Abbas as a man angling for negotiations, as not completely sold on the merits of the UN campaign. Perhaps the risk-averse Abbas was practicing a trademark of his predecessor’s governing style: pursuing multiple policy options with varying degrees of effort to varying effects. Or perhaps Abbas was cognizant of another event in history, of a time in 1999 when Arafat threatened to go to the UN at the end of the Oslo interim period and Clinton brought him back with the promise of negotiations.

Whatever Abbas’s opinion, the US did enough to dissuade a Security Council vote through the veto, but not enough to circumvent a General Assembly vote in 2012. Upgraded status and moniker in hand, the Palestinians in 2012 had taken another step on a road they started nearly forty years ago.

This report will detail how the Palestinian leadership created, implemented, and assessed their UN campaign. It will analyze this UN campaign in the broader context of a shift in Palestinian strategy, of the calls within the leadership for a more consolidated, integrated approach to attaining statehood, and what the next steps are if the talks set up by John Kerry in the summer and fall of 2013 fail.