Research

/ Israel and Europe

Research

/ Israel and Europe

The European Union’s response to the war in Gaza has been widely criticized as irrelevant and incoherent, casting doubt on its ability to become a credible player in the region. While the EU is indeed incoherent, it is not entirely irrelevant. Its chief relevance lies in the civil sphere, mainly through its efforts to sustain and encourage reforms in the Palestinian Authority, and its role as a capacity builder. These EU actions and capabilities have political significance for the “day after” the war. The EU has many tools it can use in the region but has yet to show a collective willingness to fully employ them, because of internal divisions and the multiplicity of voices within it. The paper reviews these spheres of cacophony and maps the realignment of camps within the EU in response to the war in Gaza.

This article was published in the Strategic Assessment of the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), Issue 27 (4), November 2024.

Introduction

Less than a week after October 7, some analysts were quick to argue that “the Israel-Hamas war exposed the EU’s irrelevance” (Karnitschnig, 2023). “No one cares what Europe thinks” continued the harsh assessment. “Europe has been relegated to the role of a well-meaning NGO, whose humanitarian contributions are welcomed but is otherwise ignored.” Many in Israel, Europe and around the world would agree, yet we wish to present a more nuanced picture. Unlike in Ukraine, Europe struggles to find a strong, united voice regarding the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza. The EU’s incoherence significantly reduces its capabilities as a credible player and prevents it from taking a meaningful role while the war expands. Yet Europe is relevant as a mid-level player in the reform of the Palestinian Authority, the rebuilding of Gaza, and in wider efforts to resolve the Israeli Palestinian conflict.

In 2018, then president of the EU Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, asserted that it was not enough for Europe to exert its financial muscle. It also had to learn to act on the global stage: “The EU is a global payer, but must also become a global player” (European Parliament, 2018). Josep Borrell, the High Representative (HR) of the EU for Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), argued in 2019 that Europe “must learn quickly to speak the language of power,” and not only rely on soft or normative power as it used to do (European Union External Action, 2020). Over the past three decades, the EU has been one of the main donors to the Palestinians. It became a significant actor in the civilian sphere, but not a meaningful political player in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and certainly not in the realm of security (See Hollis, 1997, Bouris, 2014 for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. On the EU’s lack of actorness, see Toje 2008). What has changed (if at all) since October 7?

This paper focuses on the European response to the war in Gaza and the hostilities towards Israel in the wider region. Although it concentrates on the EU, there is also a brief discussion of actions taken by other European countries, mostly the United Kingdom (UK). It aims to give an empirical description and analysis of Europe’s responses, capabilities and actorness in this regional war. The article begins with the shifting European positions from strong support and solidarity with Israel after the October 7 massacre, to fierce criticism of Israel and its government. The second section maps where the EU is a mere payer and where it is a player. It reviews the EU’s decisions and actions in the humanitarian field, Palestinian state-building, the diplomatic arena, its employment of “sticks” and sanctions and the military sphere. The third section discusses the divisions afflicting the EU which have hampered its ability to act as a meaningful player in the region. It reviews the instances of discordant voices within the European Commission, between heads of EU institutions and mostly between member states on multiple issues, and maps the realignment of camps in Europe on the conflict. In the conclusions, the article evaluates the EU’s response to the war in Gaza, its capabilities and actorness in the Gaza war. It argues that the EU has been able to chalk up some accomplishments in less sensitive areas, most noticeably as a capacity builder in the Palestinian Authority. Its financial muscle has come to the fore in important humanitarian activity and especially in working to prevent the financial collapse of the PA. Europe has also carried out operations to enhance maritime security in the wake of attacks by the Houthis. Despite divisions which prevent it from becoming an effective actor in the Israeli-Palestinian arena, it still has an important role to play.

The EU and the War in Gaza: From Support to Criticism of Israel

Europe’s solidarity with Israel in the wake of the Hamas massacre of October 7 and kidnapping of more than 250 civilians and soldiers, was remarkable. It was immediate, extensive, and strong. Political support came from across Europe. There was fierce condemnation of Hamas from across the board. All EU member states supported Israel’s right to defend itself. The strong solidarity with Israel was demonstrated through numerous declarations, visits, and actions.

For a few weeks, the Gaza war took precedence over the war in Ukraine on the EU’s agenda. Manifold statements, speeches, Foreign Affairs Council (FAC) declarations, and European Council conclusions condemned the Hamas attack in the strongest terms (European Council, 2023). An unprecedented European Parliament (EP) resolution called for the elimination of Hamas with 500 votes in favor and 21 against (European Parliament, 2023a). These verbal expressions of support were important to Israel and gave it legitimacy for the war against Hamas.

Many heads of state as well as foreign and defense ministers from all across Europe visited Israel within a matter of weeks in an impressive show of solidarity. They travelled to the south of Israel to witness the devastated communities, they met with relatives of the hostages and restated Israel’s right to exercise self-defense. Among the first to arrive, on October 13, were the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and the President of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and French President Emmanuel Macron all visited Israel between October 17-24 to express their solidarity with the Israeli people. Several weeks later HR Josep Borrell visited. This was his first visit to Israel since he assumed his mandate in 2019 (Lis, 2023). Between October 7, 2023 and May 2024, about 80 out of 100 high level visits to Israel were from Europe (Meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Europe Division, June 23, 2024). Israelis felt they were not alone.

Yet, as the war in Gaza continued, European support for Israel gradually declined. Support for Israel’s right to defend itself is on condition that civilians are afforded protection in accordance with international law and international humanitarian law (IL & IHL). Amid the growing number of Palestinians killed in Gaza and the increasingly acute humanitarian situation there, the mood in Europe gradually turned against Israel. In addition, the refusal of Netanyahu’s government to accept a cease-fire, or discuss plans for the “day after” the war, its outright rejection of a role for the Palestinian Authority (PA) as an alternative to Hamas in Gaza and its fierce opposition to the possible establishment of a Palestinian State in the long run, have created great difficulties for Israel’s friends in Europe, since both the EU-27, the UK and Norway support the establishment of a Palestinian State.

The international legal cases against Israel make it more difficult for Europe to support it, especially under its current extreme right-wing government. In December, South Africa petitioned the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which is now investigating claims that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. In May, the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor applied for arrest warrants for Prime Minister Netanyahu and Minister of Defense Gallant. In July, the ICJ published its advisory opinion on Israel’s ongoing occupation of the Palestinian territories (case opened in 2022). IL & IHL are normative pillars of the EU’s foreign policy. Moreover, in view of Europe’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war, where it has demanded that Russia adhere to IL & IHL and has imposed extensive sanctions on Moscow, and despite the major differences between the war in Ukraine and that in Gaza, the EU has been accused of applying double standards regarding Israel’s conduct in Gaza. This harms the EU’s reputation and interests in the Global South.

Europe’s solidarity with Israel and its delayed call for a ceasefire have strained its relations with countries in the Global South. Europe has worked hard since February 2022, reaching out to these countries in order to mobilize support for Ukraine. The alarming death toll in Gaza and the severe humanitarian situation sabotaged Europe’s efforts. Equating these two wars is problematic (Navon, 2024), but this doesn’t prevent some in the Global South and in Europe from doing so. As Konečný (2024) points out:

Efforts to convince [the Global South] that Europe’s… support for Ukraine against Russian aggression was based on universal principles of international law rather than the West’s geopolitical agenda, were squandered when the West veered off those same principles in Gaza.

Borrell concedes that this is a problem for the EU, and that he is regularly confronted with accusations of double standards:

What is now happening in Gaza has portrayed Europe in a way that many people simply do not understand. They saw our quick engagement and decisiveness in supporting Ukraine and wonder about the way we approach what is happening in Palestine… The perception is that the value of civilian lives in Ukraine is not the same as in Gaza, where more than 34,000 are dead, most others displaced, children are starving, and the humanitarian support [is] obstructed. The perception is that we care less if United Nations Security Council resolutions are violated, as it is the case by Israel with respect to the settlements, [as opposed to] when it is violated by Russia. (EEAS Press Team, 2024a).

Europe’s credibility and its ability to forge a wide international coalition against Russia is undermined by the perception of countries in the Global South that Europe’s attitude towards the war in Gaza is an embodiment of its double standards. Support for Israel by some European countries exacts a price for the whole EU, impacting its relations with the Global South, and its case for and reputation as a supporter of Ukraine.

The EU’s Role—From Payer to Player?

The EU has taken concrete steps in several fields in an attempt to transform itself from a mere payer in the conflict to an actual player. It seeks to intervene and influence by applying leverage on some actors, especially by exerting its financial muscle. In addition, the EU has conducted a defensive operation to intercept Houthi attacks on ships, and has taken steps to crack down on the financing of Hamas. It adopted sanctions against violent Israeli settlers aimed at impacting the wider Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But its main intervention comes in its significant role in financially sustaining the PA and conditioning its contributions on substantial and comprehensive PA reforms, alongside agreed US-EU conditions for the PA to return to rule in Gaza (see below).

The Humanitarian Field: Significant Payer, Attempts as a Player

There is no doubt that the EU is a significant payer. Humanitarian aid provided by the 27 member states to the Palestinians from October 7 until September 2024 was more than quadruple its level in the equivalent period preceding the war, reaching €678m, while EU aid increased ninefold from €28m to €262m (European Parliament, 2023b; Reuters, 2023). For comparison, in the same period the US donated $1 billion to the Palestinians. (USAID, 2024b).

The European Commission and a number of EU member states also tried to become more actively involved, by forging a multilateral force which facilitated a new pathway for humanitarian aid. In March, the European Commission, Cyprus, the US and the United Arab Emirates launched the Amalthea Initiative, operating a maritime route for emergency assistance from Cyprus to the northern part of the Gaza Strip. The initiative was proposed by Cyprus less than three weeks after October 7 (Politico, 2023) but was implemented only in March 2024 amid an increasingly acute humanitarian situation in Northern Gaza. The US was the key player in implementing the project in Gaza, building the jetty, while Europe established the Joint Rescue Coordination Center in Larnaca. Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK all participated in the operation ( ECHO (European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, 2024).

The gap between expectations and implementation of the Amalthea Initiative was considerable. There were high expectations that at full capacity, the route could facilitate the transfer of humanitarian assistance for at least 500,000 people (USAID, 2024a), yet the quantities of aid delivered were very small (7000 tons, equivalent to only 350 trucks, or a day and a half of aid transferred by land). Between May and July, the jetty operated for only 12 days due to bad weather and the need for repairs, while its building costs were over $230 million. Several European ships delivered cargo to the jetty, which was distributed by aid organizations in the Strip. The jetty was eventually dismantled by the US at the end of July (Cleaver, 2024). The maritime route was diverted to Ashdod port and aid continued to enter Gaza via land crossings. In effect, the Amalthea initiative made only a cosmetic difference to humanitarian efforts and contributed little to Europe’s actual role.

Palestinian Statehood—Significant Payer and Possibly a Significant Player

The EU’s financial assistance to the Palestinians testifies to its potential to become a more significant player. In addition to humanitarian aid, the EU is the biggest provider of external assistance to the PA, with over €1.2 billion originally planned for 2021-2024 (European Commission, 2023). This gives the EU potential leverage over the PA. While it has been reluctant to use it in the past, this now appears to be changing.

The PA depends upon Israel to collect import taxes on its behalf, which constitute 64 per cent of the Authority’s total income. The EU’s increased payments to the PA are an attempt to counter the Israeli government decision to confiscate parts of Palestinian tax revenue. This policy, led by Finance Minister Smotrich, dates back to January 2023 and is justified as a consequence of PA payments that incentivize terror by rewarding families of Palestinians in Israeli jails and those who killed Israelis. After October 7, the part of the budget that the PA routinely transferred to Gaza was also confiscated by Israel (Times of Israel, 2023; Gal, 2024). The PA has been in a dire financial situation for many years and the confiscation of funds could bring about its collapse. This would destabilize the West Bank and the region even further. After the EU and its member states invested so much in building the PA as the institutional backbone of a future Palestinian State and enhancing systems of governance, their role as payer has come to the fore and heightened their significance as a player.

In July, the Directorate-General for Neighborhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR), which oversees support programs in Europe’s Eastern and Southern areas, signed a “Letter of Intent” to the PA, announcing a €400m emergency package of aid to it to be paid until September, conditioned upon reforms in eight fields (DG NEAR, 2024a,b). In addition to playing a significant role in preserving the PA, the EU is using its financial leverage to pressure the PA to carry out reforms by employing conditions to the funding (as it does with states seeking to join the EU). The EU has significant experience and expertise in state building in general and with the PA in particular. It could use its financial muscle to help restore the independence of the Palestinian judicial system and de-radicalize and reform its education system (Tzoreff, 2024); although the latter is best done in cooperation with the UAE and Saudi Arabia. If its efforts to revitalize the PA succeed, the EU’s credibility as a player in the region would be strengthened. Such careful conditionality can build trust with Israel and could therefore enable the EU to play a more meaningful role not only vis à vis the PA, but also in the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Capacity Builder for the Day After the War—Established Player

The EU has been advancing Palestinian statehood via capacity building for a few decades. A month after October 7, the US, EU and UK were aligned regarding the basic conditions for a ceasefire leading to a long-term sustainable plan for the day after the war in Gaza. It included the return of the PA to Gaza (Gal and Sion-Tzidkiyahu, 2024). To date, the Israeli government has not agreed to their proposals, but preparations on the European side have begun nevertheless. For example, on May 27, the FAC agreed in principle to reactivate the civilian Border Assistance Mission for the Rafah Crossing Point (EUBAM Rafah), which operated out of Rafah until Hamas took over the Strip in 2007. The EU appeared to be willing to reactivate it, but needs the approval of and coordination with the PA, Egypt and Israel (FAC 2024). According to reports, Israel rejected this option (Barel, 2024). To gain agency, the EU needs to prove itself as a credible player, and to engage and build trust with Israel.

The mandate of the EU police and rule of law capacity building operation in the PA (EUPOL COPPS), already includes the Gaza Strip but it too has stopped operating there since Hamas took over. Its operative plans may be expanded as part of the PA revitalization process ahead of its possible return to the Gaza Strip (Sion-Tzidkiyahu 2024a). Through such missions, the EU can function not only as a payer but also a mid-level player. These missions can be a core component of EU civil boots on the ground in the Palestinian arena.

The (Failed) Diplomatic Front

Europe has been active on the diplomatic front, proposing several initiatives, none of which was acted upon. Only one tool was adopted by the European Council. On October 27, Spain pushed to include in the European Council conclusions support for convening a peace conference (European Council, 2023). Although the move appeared disconnected from reality on the ground, it was in accord with Borrell’s diplomatic objectives. Indeed, Borrell was the source of several diplomatic initiatives. They should be viewed in the context of his Peace Day Effort Initiative—trying to incentivize the resumption of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process—that was launched in September 2023 but halted by the war (Sion-Tzidkiyahu 2024a).

In January 2024, Borrell put forward a twelve-point non-paper for “creating a comprehensive peace plan,” proposing to hold a preparatory peace conference which would involve the pragmatic Arab states (Psara & Liboreiro, 2024). On January 22, Borrell invited the foreign ministers of four Arab states, Israel and the PA for separate discussions at the FAC. His initiative was discussed, but did not progress. Facing internal objections by member states, the initiative failed to get off the ground. In addition, the Biden Administration stayed silent regarding the plan, probably in part due to Israel’s rejection of the initiative. It didn’t help that Borrell was perceived as being strongly pro-Palestinian to the extent that some heads of state told him that he did not represent them (Moens et al., 2024), while others described him as “obsessed” with the issue.

In another diplomatic initiative on May 27, Borrell invited the foreign ministers of Egypt, Jordan, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar (known as the “Arab Quint”) to the FAC. The discussion focused on finding a political solution to the conflict and potential pathways of cooperation as a means to resolve it. Borrell used these meetings and initiatives to strengthen EU-Arab relations, seemingly to enhance the EU’s actorness, though it was clear in advance to all sides that nothing concrete would come out of these sessions.

The next meeting took place in Madrid on September 13. It aimed to discuss “the need to reinforce the engagement of the international community on peace and security in the Middle East, and the challenge of creating an international consensus on a way forward based on the Two-State solution” (EEAS Press Team, 2024c). In effect, it demonstrated the lack of consensus, as only four European foreign ministers participated (Spain, Ireland, Slovenia and Norway) along with the PA and five Arab countries.

More serious efforts were made to prevent military escalation between Israel and Hezbollah. France played a leading role working for de-escalation. Europe has an interest in preventing Lebanon from becoming a failed state. It also wants to prevent the expected refugee flows resulting from a war between Israel and Lebanon. On June 13, President Macron said that France and the US had agreed in principle to establish a trilateral group with Israel to “make progress” on a French proposal to end the violence on the Lebanese border (Boxerman et al., 2024). Yet Israel has not always been willing to accommodate French or European diplomatic engagement in this sphere. Over the past year, Hezbollah argued that the key to ending the battle in Lebanon was the achievement of a ceasefire in Gaza, which in turn depends largely on agreement between Hamas and Israel on the release of all hostages. Later in the war in Lebanon, Israel sought to break this linkage. In summary, Europe is on the sidelines of diplomatic initiatives to resolve the war in Gaza and in Lebanon. What France and Europe did demonstrate was their financial role, gathering $1 billion for Lebanon in October 2024.

Employment of Sticks and Sanctions Regimes

President Macron’s proposal to build an international coalition against Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), along the lines of the coalition against ISIS, did not gain traction (France 24, 2023). Yet France hosted a multilateral meeting in Paris on December 13, to enhance the financial war against them, by targeting the sources of their funding, and took action to stem the spread of terrorist content online (France Diplomacy, 2023). After the EU designated Hamas and PIJ as terrorist organizations in 2003, on January 19, 2024, the Council of the EU adopted a package of additional sanctions against them, including a freeze on the assets of several of their military leaders, among them Yahya Sinwar (Council of the EU, 2024a). This decision allowed the EU to take actions against additional individuals and entities supporting, facilitating, or enabling violent actions by Hamas and the PIJ. Yet enhancing its role through further intervention, for example, against straw companies in Turkey, did not ensue.

The EU did extend the sanctions list in June, adding six individuals and three entities (Council of the EU, 2024b). For the first time, sanctions were also imposed against violent Israeli settlers and some of their organizations in the West Bank. The process of imposition proved slower and more complicated politically for the EU than for its counterparts or its member states. The US imposed a first round of these sanctions on February 1, expanding them on March 14. The UK and France followed suit a couple of weeks later. It took the FAC until March 18 to cross the high threshold of unanimity and overcome Czech and Hungarian opposition. When the list of sanctions was published by the Council on April 19, it included four individuals and two organizations (Council of the EU 2024c,d ). The second round of EU sanctions came only on July 15, adding five individuals and three organizations (Council of the EU, 2024e). Those listed under the EU sanctions regime are “subject to an asset freeze, and the provision of funds or economic resources, directly or indirectly, to them or for their benefit, is prohibited.” Additionally, the EU imposed a travel ban on the sanctioned individuals. The slow pace of the sanctions adopted is indicative of the EU’s political difficulties in crossing what was considered a red line in its policy vis a vis Israel. Yet it was crossed.

The EU has considerable economic leverage with Israel as its largest trading partner. So far, the EU has shown little willingness to use its leverage vis à vis Israel inside the 1967 lines as the threshold of unanimity for such action in the FAC or European Council is too high (see disagreement regarding the Association Agreement below). The war has prompted the re- or over-politicization of relations in all areas of cooperation, in addition to the rise of anti-Semitism and anti-Israeli attitudes, including latent or vocal grassroots boycotts and lost opportunities. For example, it is unlikely that the EU would be able to sign a Partnership Priorities agreement with Israel anytime soon. It is also probable that a new UK-Israel trade agreement, currently under negotiation, would pose greater political challenges for the Labour government to sign.

The relative ease of taking decisions at the national level, in comparison to the EU level, is noticeable. Some European countries have shown greater readiness to impose bans on arms sales to Israel. In February, a Dutch court ordered the government to block the delivery of US-made F-35 fighter aircraft parts to Israel, over concerns they were being used to violate international law. Yet the government appealed, and meanwhile sent the parts to the US, where they were sent to Israel. Three European states took steps to fully suspend military exports to Israel: Spain, Italy and the Walloon part of Belgium. The UK, Denmark and Germany examine the export licenses on a case-by-case basis. Of the above, Germany’s stance is most significant: 30 per cent of Israel’s arms were imported from Germany and 69 per cent from the United States between 2019 and 2023 (Bermant 2024a; Sion-Tzidkiyahu 2024d). Therefore, the damage caused by other European countries’ arms ban is felt less in the military-security sphere and much more in the political and diplomatic domain. This is illustrated by President Macron’s call in early October 2024 for a weapons embargo on Israel, although he referred only to the war in Gaza, not the one with Hezbollah and other Iranian proxies. In addition, France prevented Israeli companies from participating in the June 2024 Eurosatory international arms fair, although a number of Israeli companies did participate in the Euronaval defense exhibition which took place in November 2024.

Defensive Military Role

To the extent that Europe is even playing a military role, there is a clear distinction between the UK and the EU. Right after October 7, Britain joined the US in dispatching military forces to the Eastern Mediterranean to support Israel and deter Hezbollah and Iran from a full-scale attack on Israel. In addition, both Britain and France were involved in the interception of Iranian attacks against Israel in April and later in October (Times of Israel, 2024).

The EU’s military role emerged in response to the Houthis’ trade route disruption in the Red Sea. Since the Houthis began their offensive on November 19, they have attacked over forty ships in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Targeted strikes by the US and the UK against Houthi bases began on January 11. The EU launched operation EUNAVFOR Aspides on February 19. However, unlike the US and UK, the EU’s rules of engagement are defensive. They aim only to protect merchant shipping and restore freedom of navigation and exclude direct attacks on Houthi positions. This sea route from Asia through the Suez Canal to Europe accounts for twelve percent of global trade and is of special significance to Southern European Mediterranean countries. Alternative sea routes double shipment costs at a time when inflation has already been high in the EU and the cost of living is a sensitive social and political issue.

As of July, five European frigates had escorted over 170 merchant ships and intercepted nineteen Houthi missiles and drones (Al-Batati, 2024; EEAS Press Team, 2024b). By aiming to secure the Suez Canal route, the EU’s operation is also crucial for Egypt and the region’s economy. Through this operation, the EU enhances maritime security, furthers the protection of European, regional and international commercial interests, or at least mitigates to some extent the economic damage caused by the Houthis, while strengthening its joint military cooperation capabilities under EU command (Matoi & Caba-Maria, 2024). The success of the EU military operation as well as that of the US and the UK, is limited at best. Maritime traffic has stabilized since January at 50-60% of levels in equivalent months in 2023 (Gard, 2024).

Europe’s Tendency for Cacophony

Immediately after October 7, alongside the strong and widespread demonstrations of European solidarity with Israel and fierce condemnation of Hamas, there were many issues where the EU did not speak with one voice. The cacophony started within the European Commission, followed by open disagreement between heads of EU institutions and then between member states on issues such as funding for the Palestinians, calls for a ceasefire, recognition of a Palestinian state, South Africa’s ICJ case against Israel and the issue of payments to UNRWA. This cacophony hampers the ability of the EU to play a meaningful role.

Within the Commission, the difficulties started with the Hungarian commissioner for neighborhood policy, Olivér Várhelyi, who tweeted on October 9 that aid to the Palestinians would be cut. A few hours later, the Slovenian Commissioner for crisis management, Janez Lenarčič, tweeted that humanitarian aid would actually be doubled. He was echoed by HR Borrell who asserted that the EU should support the Palestinians “more, not less,” stating that this is the position of 95 percent of EU member states. Borrell stressed that the EU differentiates between terror organizations such as Hamas and the PIJ, and the PA and Palestinian civilians. Later that day, the Commissioner spokesperson clarified that there would be no aid cuts. Instead, the Commission decided to review its payments to the Palestinians, in order to ensure that no funding was reaching Hamas or the PIJ (Moens et al.2023). This review process ended in November 2023 with the decision to continue payments and, as mentioned, increase them (European Commission, 2023).

Between Heads of EU Institutions

The president of the European Council, Charles Michel, criticized the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, for stating in her press conference with Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu in October 2023 that Israel had the right to defend itself, without adding that it must be done in accordance with IL & IHL. According to Michel and others, this failure to state the EU’s core values was a reflection of her pro-Israeli stance. She was accused of overstepping her powers, not representing the EU’s interests properly, “undermining the position of the EU as credible actor and honest broker between Israeli and Palestine,” projecting the image of double standards to the Global South (Borges de Castro, 2023). Also, in an unusual move, 850 employees of EU institutions published a letter complaining about von der Leyen’s omission (Agence Europe, 2023).

There are also significant differences between EU member states. On the issue of a ceasefire, on October 27, the heads of 27 member states in the European Council agreed on phrasing that called on Israel to allow “humanitarian corridors and pauses for humanitarian needs” (European Council, 2023). It took them hours to reach an agreement on “pauses,” in plural, to avoid the impression that they were calling for a permanent pause. On that very same day, the EU member states split into three camps over a UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution, calling for an “immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce leading to a cessation of hostilities” and condemning terrorism. Eight member states voted in favor, fifteen abstained and four voted against the text, as it did not mention Hamas or the October 7 massacre (UNGA, 2023; Alessandri & Ruiz, 2023). These divisions demonstrated once again the difficulties for the 27 member states to speak with one voice on the details of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Analysis of the EU’s UNGA voting on the Palestinian issue shows unanimous agreement among the 27 member states and the UK on the end goal of the “right of the Palestinians to self-determination” and “on permanent sovereignty of the Palestinian people in the occupied territories” (two decisions adopted on December 19). Yet when it came to the more practical vote calling for a ceasefire on December 12, or the admission of Palestine as a UN member state on May 10, the EU was split again into three camps. Overall, on eight resolutions between October 7 and May 10 relating to the Palestinian issue and the war in Gaza, the EU stayed united on only three occasions (Sion-Tzidkiyahu, 2024b). As this analysis suggests, Europe is united when it comes to supporting the two-state solution, yet it is divided on the translation of that goal into concrete policy.

In the wake of Israeli charges that some of UNRWA’s employees participated in the attacks of the October 7 massacre (UNRWA, 2024), EU member states were also split on the question of whether to freeze UNRWA’s funding. The EU and eleven European countries (among them the UK) briefly suspended the funding, while eight did not (Sion-Tzidkiyahu, 2024c). Further cacophony continued upon the resumption of funding. The EU attached three conditions to renewed UNRWA funding, which could have served to apply its normative power, or at least lead a united voice for all the funders of UNRWA. Yet, the EU was unable to put its own house in order, the conditions adopted by each member state were different, and most did not adopt any.

South Africa’s case against Israel in the ICJ is another example of division. Germany announced it would intervene on Israel’s behalf as a third party. Another five EU member states (Austria, Czech Republic, Italy, Hungary and France) expressed their support for Israel. The UK joined them. Ireland, Slovenia, Belgium and Spain joined in support of South Africa. Other member states only called on Israel to comply with its rulings and with IL and IHL (Sion-Tzidkiyahu 2024c).

On February 14, the prime ministers of Spain and Ireland sent a letter calling on von der Leyen to carry out an urgent review of whether Israel was complying with its obligations to respect human rights, which constitute “an essential element” of the EU-Israel Association Agreement. They requested that appropriate measures be taken if Israel was found to have breached them (Lynch, 2024). The Association Agreement is the basis for EU–Israel relations in all fields: trade, economic, political dialogue and participation in different EU programs, such as Horizon Europe and Erasmus. This was the first time such a demand had been made at the level of prime ministers. Nevertheless, differences of opinion meant that the request was shrugged off at the FAC which met on March 18.

On May 27, 2024 the FAC for the first time engaged in a “significant” discussion on steps against Israel if it didn’t comply with IHL (Weatherald, 2024). That was after the ICC submitted applications for arrest warrants against Netanyahu and Gallant on May 20, and the ICJ intermediate ruling on May 24 that Israel should adhere to IHL in its operation in Rafah. According to the foreign minister of Ireland, Micheál Martin, “there was a very clear consensus about the need to uphold the international humanitarian legal institutions,” i.e. the ICJ and ICC. Yet the FAC’s sole conclusion was to hold an EU-Israel Association Council meeting with Foreign Minister Katz to address the EU’s serious concerns and seek Israel’s response on ICJ compliance. Despite the calls from Ireland and other member states, no sanctions paper against Israel was drawn up. So far, the letter achieved little more than headlines and an unpleasant invitation to Katz.

The recognition of a Palestinian state is a major point of division in Europe. While there is consensus on the two-state solution, opinions differ on how and when to advance it. On January 30, British Foreign Minister Cameron was the first to publicly consider recognizing a Palestinian state since October 7. French President Macron, Italian Prime Minister Meloni, and senior heads in Germany also indicated they were considering it, but no actions were taken. On May 28, Spain, Ireland, and Norway recognized Palestine, followed by Slovenia on June 5, making it the 147th state and the 11th in the EU to do so (excluding Sweden’s 2014 recognition, earlier recognitions date back to 1988 and were by former Communist states, and Cyprus which was not an EU member then). Belgium and Denmark chose not to recognize Palestine. While such recognition can yield domestic and international political benefits, it is largely symbolic for Palestinians and leave realities on the ground unchanged. This cacophony demonstrates again that Europe agrees on the concept of two states for two peoples, but remains divided on how and when to pursue this goal.

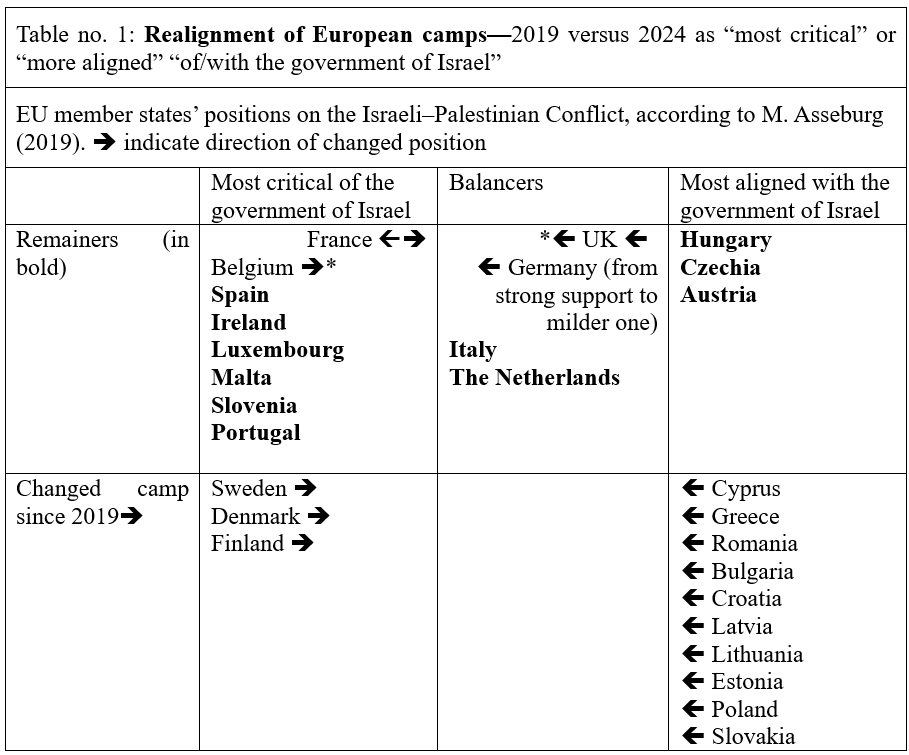

Realignment of Camps

A year after October 7, the Czech Republic and Hungary continue to express strong support for Israel. The UK, Germany, Greece, Cyprus, and some Central European countries, which offered firm support for Israel, adopted a more nuanced stance in the months that followed. All stressed the importance of complying with IL & IHL in the Gaza Strip. When Israel’s security was on the line, as happened in mid-April and again in early October, the UK and France actively participated in thwarting Iran’s missile attacks, underlining their position that Israel has the right to defend itself.

Spain, Ireland, Belgium, Slovenia, and Malta were quick to restate their critical position of Israel, with Spain and Ireland calling for a reassessment of the EU-Israel Association Agreement. Both formally recognized the Palestinian state with Norway and Slovenia.

Germany’s long-standing historic responsibility to Israel’s security, Germany’s Staatsraison or raison d’état, is being tested. This commitment has been inserted in coalition agreements in Germany since 2008, including by the current SPD-Green-Liberal government. Despite criticism of Israel, Germany has maintained support for the country. However, amid accusations that Israel has breached IL and IHL, Germany has shown a readiness to reexamine its continued sale of military exports to Israel, including the possibility of delaying the supply of certain items.

Ultimately, the normative traditions and narrow self-interests of the government in each European state are what count in the formulation of policy towards Israel and the Palestinians, rather than the need to maintain a united harmonious and coherent European response. Given the mix of normative and interest-based approaches, consensus has been hard to achieve in the FAC or European Council. This represents the “old” CFSP, in contrast to the brisk and assertive EU response to Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Alignments may shift due to elections, as was seen in Belgium in June and the UK in July, where the new Labour government under the leadership of Keir Starmer has already dropped its opposition to an international arrest warrant for Netanyahu and Gallant. His government has also suspended 30 out of 350 arms export licenses to Israel (Bermant, 2024b). However, Starmer has ruled out a complete ban on UK arms exports to Israel, saying it “would be the wrong position for this government” (Hardman, 2024).

In the past years, under Netanyahu, Israel has strengthened ties with Greece, Cyprus, and some Central and Eastern European countries, such as the Baltic states, Romania and Bulgaria, using these alliances to counter unfavorable EU votes. Netanyahu’s “divide and thwart” diplomacy harnessed the support of friendly member states to block or soften anti-Israel decisions (Sion-Tzidkiyahu, 2021). This tactic has been effective when the Israeli-Palestinian conflict featured less prominently on the global agenda, or when initiatives with considerable implications come to the fore, such as reassessing the EU–Israel Association Agreement. However, during the war in Gaza, this strategy has been effective only up to a point. For example, it did not prevent sanctions on violent Israeli settlers and their organizations. The EU’s emphasis on IL & IHL is highlighted by the Russia-Ukraine conflict. With the ICJ’s judgement on Israeli occupation, South Africa’s proceedings on Gaza, and the ICC request for warrants against Netanyahu and Gallant, the EU and its member states’ room for maneuver vis à vis Israel in the Gaza war is shrinking.

* Change after general elections

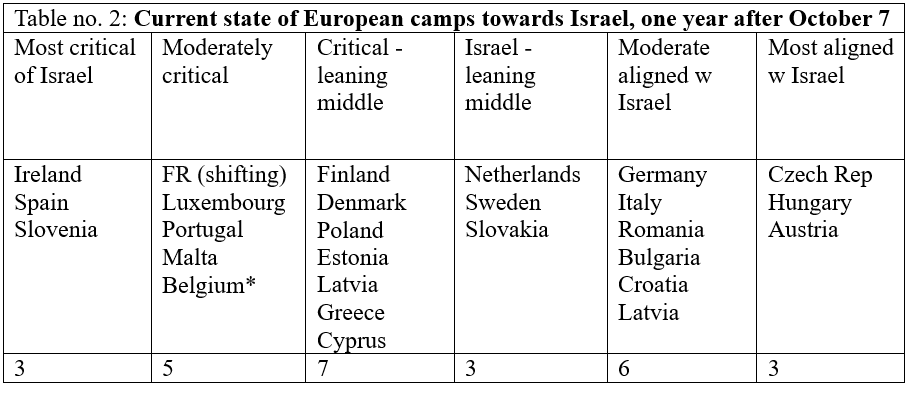

The result, one year after the war is the following continuum, from the most critical of Israel to the most supportive:

The current realignment of camps regarding Israel is much more complicated than it was before October 7. It reflects not only the lack of an Israeli-Palestinian peace process, Israeli occupation and settlement building; but now encompasses Israel’s security, its right to defend itself against Iran and its proxies, and its struggle for legitimacy.

Conclusions

In the aftermath of October 7, the EU initially showed strong solidarity with Israel in its darkest hour. Yet as the civilian death toll in Gaza rose and the humanitarian situation deteriorated, most of Europe’s leaders began distancing themselves from the Israeli government and expressed increasing criticism. Despite general agreement on the two-state solution, the divisions on how and when to proceed in this direction paralyze the EU. The Gaza War demonstrated once again the difficulties of the 27 member states in speaking with one voice on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Due to the need for consensus, the only agreed action by the EU was to impose sanctions on violent Israeli settlers and their organizations. The rest of the moves were taken by small groups of member states: some joined South Africa’s ICJ case against Israel, four countries recognized Palestine as a state and a couple requested a reassessment of the EU-Israel Association Agreement.

The Gaza war has revealed once again the divisions, cacophony and ponderous decision-making characteristics of the EU in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In August, Borrell conceded that “the Palestine-Israel conflict is one of the most difficult issues to build EU27 consensus on, probably more than on any other issue” noting it as the stumbling-block to effective intervention (Scheindlin, 2024).

So what has changed (if at all) since October 7 in the EU’s actorness? Seemingly not much. The EU has a range of financial and civilian tools to offer today and for the day after the war. It is a considerable humanitarian payer, though less of a player on the ground. It is a significant actor in Palestinian capacity and state building, willing to reactivate EUPOL COPPS in Gaza and EUBAM at the Rafah border crossing. Their renewal could enhance the EU’s role alongside its participation in the rebuilding of the Gaza Strip the “day after”.

The EU is already playing a significant role in the West Bank. At a time when elements in the Netanyahu government are acting openly to bring about the financial collapse of the PA, the EU’s role as a stabilizer in funding the PA and preventing its collapse is vital. This is essential for preserving the two-state solution and helping to prevent a major conflagration in the West Bank.

Taking into consideration that the EU’s diplomatic initiatives have all failed internally and were usually ignored by the US, the EU should think anew about how to strengthen its actorness. The EU’s most significant potential leverage stems from being the largest donor to the PA. By using its financial muscle to revitalize the PA through conditionality, DG NEAR, which has the ability to act consistently, could strengthen the EU’s role and credibility. This is the EU’s main potential leverage asset, depending on the scope and depth of the implementation of PA reforms and could make the EU a more credible player in Israeli eyes.

It remains to be seen how powerful and effective this conditionality will be under the next European Commission. If successful, the EU could be viewed in time as a more significant player, which would prompt Israel to take Europe more seriously and pay more attention to European concerns, rather than dismissing them. However, for this to happen, the EU would also need to engage more positively and directly with Israel’s government. The new European Commission, which took office on December 1, appears better placed to do this.

The EU has potential leverage with Israel, as its biggest trade partner, yet divisions among member states have hampered its ability to use this effectively. The war caused a considerable realignment, and many European governments have distanced themselves from the current Israeli government. The proceedings in the ICJ and ICC are raising serious questions over whether Israel’s actions in Gaza comply with IL & IHL. Rulings against Israel would reduce Europe’s room for maneuver in supporting Israel, let alone advance relations. Indeed, this support is likely to shrink further as Europe’s normative emphasis on IL & IHL aligns with its geopolitical interests relating to the Russia-Ukraine war.

In the wider regional conflict, the EU is more than just a humanitarian actor or a payer. It also acts as a modest security provider, as in the EUNAVFOR Aspides operation, where the EU attempts to restore maritime security and freedom of navigation, operating as a defensive rather than offensive player, protecting its own economic interests and those of Egypt as well as other developing countries on this trade route.

This paper analyzed Europe’s attempts to develop its actorness in relation to the Gaza war and hostilities in the wider region. These efforts have been only partially successful, and have been achieved mainly on the sidelines of the Gaza war. As the EU navigates an increasingly unstable multipolar world, it is still searching for ways to align its political influence with its economic and financial weight. Unlike the geopolitical awakening prompted by the Russia-Ukraine war, the Gaza war has not triggered a similar response. Despite the region’s security challenges and the destabilizing actions taken by Iran, its proxies, and Israel, the war in Gaza does not pose a strategic threat to Europe as does Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The EU has sought support from the Global South for Ukraine against Russia, yet the war in Gaza has undermined these efforts, amid mounting criticism of perceived European double standards towards Israeli actions in Gaza. One way to restore credibility is by laying the groundwork for the eventual establishment of a future Palestinian state. By revitalizing the PA, the EU can also strengthen its credibility and regional influence. However, the EU’s incoherence regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict reduces significantly its credibility as an actor, yet accusations that it is an irrelevance in the Middle East are wide of the mark.

References:

Agence Europe. (2023, October 21). Almost 850 European officials criticize Ursula von der Leyen’s biased stance on Middle East crisis. Europe Daily Bulletin No. 13276. https://agenceurope.eu/en/bulletin/article/13276/19

Al-Batati. S. (2024, May 19). EU Red Sea mission says it defended 120 ships from Houthi attacks. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.pk/node/2513266/middle-east

Alessandri. E. and Ruiz. D. (2023, November 14). The EU and the Israel-Hamas war: A narrow but important niche. MEI. https://www.mei.edu/publications/eu-and-israel-hamas-war-narrow-important-niche

Asseburg M. (2019). Political Paralysis: The Impact of Divisions among EU Member States on the European Role in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Mitvim, SWP & PAX.

Barel Z. (2024, May 30). The Rafah Crossing May be Israel’s Way Out of the [Gaza] Strip. Haaretz (Hebrew). https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/2024-05-30/ty-article/.premium/0000018f-c5d8-db12-a3ff-c7fe77e70000

Bermant. A. (2024a, August 1). The UK’s arms sales to Israel are tiny – but here’s why Netanyahu’s government is panicking about a possible ban. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/01/uk-arms-sales-israel-netanyahu-panicking-ban-starmer

-. (2024b, September 4). If the UK really wants to stop Netanyahu’s aggression, here’s what it should do. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/sep/04/uk-benjamin-netanyahu-labour-israel

Borges de Castro R. (2023, October 15). From a geopolitical to a ‘geo-damaged’ Commission. Euractive. https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/opinion/from-a-geopolitical-to-a-geo-damaged-commission/

Bouris D. (2014). The European Union and Occupied Palestinian Territories. Routledge.

Boxerman. A., Breeden. A., Ward. E. (2024, June 14). Israeli Defense Chief Rebuffs French Effort to End Israel-Hezbollah Fighting. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/14/world/middleeast/israel-hamas-hezbollah-lebanon.html

Casey. R. (2024, May 24). How Germany Lost the Middle East. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/05/24/germany-israel-gaza-palestine-war-middle-east-politics-soft-power-speech/

Cleaver T. (2024, July 10). Gaza aid jetty ‘to be permanently removed.’ Cyprus Mail. https://cyprus-mail.com/2024/07/10/gaza-aid-jetty-to-be-permanently-removed/.

Council of the EU. (2024a, January 19). Council Decision (CFSP) 2024/385 establishing restrictive measures against those who support, facilitate or enable violent actions by Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2024/385/oj

-. (2024b, June 28). Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad: Council adds six individuals and three entities to the sanctions list. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/06/28/hamas-and-palestinian-islamic-jihad-council-adds-six-individuals-and-three-entities-to-the-sanctions-list/

-. (2024c, April 19). Council Decision (CFSP) 2024/1175. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024D1175

-. (2024d, April 19). Extremist settlers in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem: Council sanctions four individuals and two entities over serious human rights abuses against Palestinians. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/04/19/extremist-settlers-in-the-occupied-west-bank-and-east-jerusalem-council-sanctions-four-individuals-and-two-entities-over-serious-human-rights-abuses-against-palestinians/#:~:text=The%20listed%20entities%20are%20Lehava,Elisha%20Yered%2C%20are%20also%20listed.

-. (2024e, July 15). Extremist Israeli settlers in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, as well as violent activists, blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza: five individuals and three entities sanctioned under the EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/07/15/extremist-israeli-settlers-in-the-occupied-west-bank-and-east-jerusalem-as-well-as-violent-activists-blocking-humanitarian-aid-to-gaza-five-individuals-and-three-entities-sanctioned-under-the-eu-global-human-rights-sanctions-regime/

DG NEAR. (2024a, July 17). Letter of Intent between the Palestinian Authority and the European Commission. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/letter-intent-between-palestinian-authority-and-european-commission_en

-. (2024b, September 5). EU proceeds with the disbursement of further emergency financial support to the Palestinian Authority. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-proceeds-disbursement-further-emergency-financial-support-palestinian-authority-2024-09-05_en

ECHO (European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations). (2024, March 8). Joint Statement endorsing the activation of a maritime corridor to deliver humanitarian assistance to Gaza. https://tinyurl.com/3e9ce2m7

EEAS Press Team. (2024a, May 3). Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at Oxford University about the world confronted by wars. EEAS. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/united-kingdom-speech-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-oxford-university-about-world_en

-. (2024b, July 5). Press Statement by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell during his visit to the Operational Headquarters in Greece. EEAS. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eunavfor-operation-aspides-press-statement-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-during_en?s=410381

-. (2024c, September 12). Israel/Palestine: High Representative Josep Borrell travels to Madrid for meeting on the implementation of the Two State solution. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/israelpalestine-high-representative-josep-borrell-travels-madrid-meeting-implementation-two-state_en

European Commission. (2023, November 21). European Commission: Review of Ongoing financial assistance for Palestine. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/Communication%20to%20the%20Commission%20on%20the%20review%20of%20ongoing%20financial%20assistance%20for%20Palestine.pdf

European Council. (2023). European Council Conclusions, 26 and 27 October 2023, Art. 16. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/67627/20241027-european-council-conclusions.pdf.

European Parliament. (2018, September 12). State of the union debate: Strengthen EU as a global player. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20180906IPR12102/state-of-the-union-debate-strengthen-eu-as-a-global-player

-. (2023a). Resolution of 19 October 2023 on the despicable terrorist attacks by Hamas against Israel. https://tinyurl.com/2up79348

-. (2023b). EU financial assistance to Palestine. European Parliamentary Research Service. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/754628/EPRS_BRI(2023)754628_EN.pdf

European Union External Action. (2020, October 29). Europe Must Learn Quickly to Speak the Language of Power. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/several-outlets-europe-must-learn-quickly-speak-language-power_und_en

France Diplomacy – Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, Fight against terrorism – Meeting on combating Hamas (2023, December 13, Paris). https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/israel-palestinian-territories/news/2023/article/fight-against-terrorism-meeting-on-combating-hamas-paris-13-dec-2023

France 24. (2023, October 24). Macron calls for anti-IS group international coalition to fight Hamas. https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20231024-macron-calls-for-anti-is-group-international-coalition-to-fight-hamas

Gal Y. (2024, June 16). Folly and fraud: Smotrich works to crush the PA and endangers Israel’s future. The Marker. (Hebrew). https://www.themarker.com/blogs/2024-06-16/ty-article/.premium/00000190-2097-d4b4-a7d6-e8f799cb0000

Gal Y. and Sion-Tzidkiyahu M. (2024). A Vision for Regional – International Partnership for Gaza Rebuilding and Palestinian Economic Leap. Mitvim Institute. https://mitvim.org.il/en/a-vision-for-regional-international-partnership-for-gaza-rebuilding-and-palestinian-economic-leap/

Gard (2024). Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Persian Gulf—situation update 30 September 2024. Published in April, updated in September. https://www.gard.no/articles/red-sea-situation-update/

Hardman. I. (2024, October 7). Starmer insists he hasn’t stepped back support for Israel. The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/starmer-insists-he-hasnt-stepped-back-support-for-israel/

Hollis. R. (1997). Europe and the Middle East: Power by stealth? International Affairs 73(1), 15-29.

Karnitschnig, M. (2023, October 12). Europe’s power outage. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/israel-hamas-war-europe-eu-power-irrelevance/.

Konečný M. (2024). The EU’s response to the Gaza War is a tale of contradiction and division. The Cairo Review of Global Affairs. https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/the-eus-response-to-the-gaza-war-is-a-tale-of-contradiction-and-division/

Lis J. (2023, March 15). Israel blocks EU’s foreign minister from visiting over comments on settlements. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2023-03-15/ty-article/.premium/israel-blocks-eus-foreign-minister-from-visiting-over-comments-on-settlements/00000186-e3e4-d8aa-a996-f7ef9b140000

Lynch S. (2024, February 14). Spanish, Irish leaders call on Ursula von der Leyen to review EU-Israel trade accord over human rights concerns. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/call-for-eu-review-eu-israel-trade-accord-over-human-rights-concerns-rafah/?utm_medium=social&utm_source=Twitter

Matoi E. and Caba-Maria F. (2024). European Union’s security perspectives in the context of conflict zones multiplication: The Red Sea crisis. MEPEI Institute. https://mepei.com/european-unions-security-perspectives-in-the-context-of-conflict-zones-multiplication-the-red-sea-crisis/

Meeting at Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Europe Division. (2023, June 23 2024) – One of co-authors, Maya Sion-Tzidkiyahu, was present at the meeting.

Moens. B. et al. (2023, October 10). Europe struggles to present consistent messaging on Palestinian aid. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-battles-to-present-common-front-on-palestinian-aid/.

Moens B. et al. (2024, April 16). Germany’s Scholz lashed out at EU foreign policy chief over Gaza stance. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/olaf-scholz-josep-borrell-benjamin-netanyahu-karl-nehammer-lashed-out-at-eu-foreign-policy-chief-on-gaza-stance/

Navon E. (2024, August 26). Europe can condemn Russia while supporting Israel. Times of Israel. https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/europe-can-condemn-russia-while-supporting-israel/

Politico. (2023, October 26). Cyprus Proposes to Send Humanitarian Aid to Gaza Via Sea. https://www.politico.eu/article/european-council-summit-eu-leaders-israel-palestine-hamas-ukraine-war-migration/?utm_source=email&utm_medium=alert&utm_campaign=European%20Council%20summit%20live%3A%20EU%20leaders%20meet%20amid%20Israel-Hamas%2C%20Ukraine%20wars

Psara M. and Liboreiro J. (2024, January 19). Revealed: Josep Borrell’s 10-point peace roadmap for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/01/19/revealed-josep-borrells-10-point-peace-process-for-the-israeli-palestinian-conflict. Also published here.

Reuters (2023, December 22). EU adopts 118 million euros aid plan for Palestinian Authority. https://www.reuters.com/world/eu-adopts-118-million-euros-aid-plan-palestinian-authority-2023-12-22/

Scheindlin. D. (2024, August 29). “Israel’s right to defend itself has a limit”: Top EU diplomat Borrell on Israel, Netanyahu and the Gaza War. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2024-08-29/ty-article-magazine/.premium/israels-right-to-self-defense-has-a-limit-top-eu-diplomat-on-netanyahu-settlers-gaza/00000191-9e18-d453-ab9f-fe9cfc570000

Sion-Tzidkiyahu M. (2021). The lost decade: EU-Israeli relations 2010-2020. Mitvim Institute. https://mitvim.org.il/publication/hebrew-the-lost-decade-israel-eu-relations-2010-2020-dr-maya-sion-tzidkiyahu/

-. (2024a). The EU contribution to the day after the war in Gaza (tentative title, forthcoming). Mitvim Institute.

-. (2024b). https://x.com/MayaSionT/status/1808052449225179201

-. (2024c). https://x.com/MayaSionT/status/1823736434278478240

-. (2024d). https://x.com/MayaSionT/status/1842856675839025228

Times of Israel. (2023, January 8). Withholding millions from PA, Smotrich says he has “no interest” in its existence. https://www.timesofisrael.com/withholding-millions-from-pa-smotrich-says-he-has-no-interest-in-its-existence/

-. (2024, April 14). US, UK and Jordan intercept many of the Iranian drones headed to Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/us-uk-and-jordan-intercept-many-of-the-iranian-drones-headed-to-israel/

Toje A. (2008). The Consensus—Expectations gap: Explaining Europe’s ineffective foreign policy. Security Dialogue 39(1), 121-141.

Tzoreff Y. (2024). What is a revitalized Palestinian Authority? Mitvim Institute and Berl Kazenelson https://mitvim.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/English-What-is-a-Revitalized-Palestinian-State-Yohanan-Tzoref-January-2024-final.pdf

UNGA. (2023). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 27 October. ES-10/21. Protection of civilians and upholding legal and humanitarian obligations. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4025940/files/A_RES_ES-10_21-EN.pdf?ln=en

UNRWA. (2024, August 5). Investigation completed: allegations on UNRWA staff participation in the 7 October attacks. https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/official-statements/investigation-completed-allegations-unrwa-staff-participation-7-october

USAID. (2024a, May 29). Administrator Samantha Power at a donor governments discussion on the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/speeches/may-29-2024-administrator-samantha-power-donor-governments-discussion-humanitarian-crisis-gaza

-. (2024ba September 30). The United States announces nearly $336 million in humanitarian assistance to support Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/sep-30-2024-united-states-announces-nearly-336-million-humanitarian-assistance-support-palestinians-gaza-and-west-bank#:~:text=This%20funding%20will%20also%20support,%241%20billion%20since%20October%202023.

Weatherald. N. (2024, May 27). EU foreign ministers discuss sanctions against Israel. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-foreign-ministers-sanctions-against-israel-micheal-martin/