Op-eds

/ The Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process

Op-eds

/ The Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process

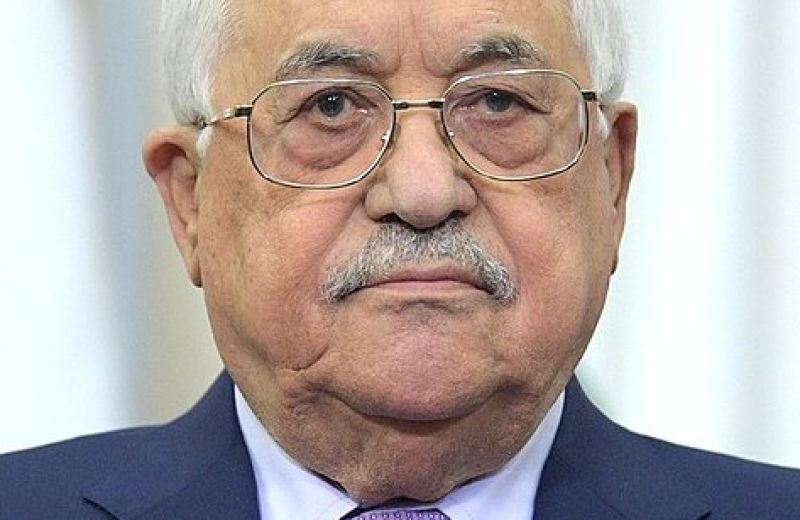

Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority’s chairman, appeared on February 20th before the Security Council and presented a new Palestinian peace plan, with a number of points: first, a request that an international conference be held until mid-2018, with the Security Council permanent members, the Quartet, Israel, the Palestinian Authority and other relevant regional players in attendance. The conference will have three resulting events: recognition of Palestine as a full member of the UN, mutual recognition of Palestine and Israel on the basis of the 1967 borders, and the establishment of an international mechanism that will help both sides discuss and resolve the open permanent issues defined in the Oslo Accords, i.e. Jerusalem, permanent borders, security, Palestinian refugees, in accordance with a pre-defined timetable and guarantees for implementing the agreed solutions.

Second, during the negotiations, the parties should refrain from unilateral actions that would hinder the implementation of the agreement, and in particular, Israel should commit to stop expanding the settlements and build new ones. Thirdly, the implementation of the Arab Peace Plan and the signing of a regional agreement after obtaining a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians. The main points of the agreement will be based on the principle of a two-state solution – Palestine, with East Jerusalem as its capital, alongside Israel within the borders of the June 4th, 1967; consent to a minimal swapping of territories of similar value and size; East Jerusalem, the capital of Palestine; A just and agreed solution to the refugee problem based on Resolution 194, formulated in accordance to the Arab peace initiative.

The timing of the announcement of the Palestinian plan is intended to preempt a possible upheaval that could stir the Palestinians upon the release of an American peace plan. Moreover, it is intended to signal, as the Palestinians have already stated more than once, that the US is no longer seen as a fair mediator in view of its unilateral stance on Jerusalem, the reduction of US aid to UNRWA and the threat of closing the Palestinian representation in Washington. From a Palestinian point of view, the imbalance created by an exclusive American mediation, can be mitigated with the involvement of international partners. In addition, the speech is intended to portray Abbas to his people as a leader who dares to challenge the US, thereby strengthening his unstable legitimacy.

In view of the thicket of corruption affairs in Israeli politics, it is no wonder that the announcement about the disclosure of the plan was accepted in Israel with indifference. The Israeli Pavlovian reaction, as expressed in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s response – “Abbas has not said anything new” – is a reminiscent of countless similar negative reactions by Israeli prime ministers and foreign ministers, including the response to the Arab peace plan in 2002. Not only that, but to ensure that Abbas is not seen as someone who is willing to make concessions, Netanyahu stressed that Abbas continues to pay millions of dollars to terrorists. Danny Danon, Israel’s representative to the UN, echoed him and said that Abbas is not part of the solution, but the problem.

The importance of the Palestinian plan is not in its content; it is anyway very general and does not contain any details, which are planned to be determined during long and exhausting negotiations. Its importance is three-fold: first, it stresses – once again – Abbas’s commitment to a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders and a possible exchange of territories, thereby refuting the claim that Abbas intends to demand the implementation of the partition boundaries of 1947. The fact that Abbas views the Balfour Declaration as illegitimate does not change the fact that he recognizes and willing to accept the existing reality. The Palestinian narrative that rejects the Balfour Declaration will not change even after a peace agreement is achieved.

Second, Abbas’s insistence on East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital shows, by inference, that Abbas recognizes West Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Thirdly, his view of the Palestinian agreement as a milestone to an Israeli-Arab peace agreement and part thereof, as expressed in the Arab peace initiative, signals that the advancement of IsraeliArab reconciliation cannot replace or advance an Israeli-Palestinian agreement.

In August 1981, shortly after Saudi Crown Prince Fahd published his first peace initiative (the first Saudi initiative) – which was immediately rejected by Israel – Yoel Marcus, a senior Ha’aretz journalist, wrote that Israel had always been able to respond to Arab bomb-bearing missiles, but not to missiles bearing peace plans. His observation was correct, but not accurate. Israel has learned to intercept both bomb-bearing missiles and peace plans. It does so by simply ignoring, opposing, or announcing that they are a recipe for the destruction of Israel.

Abbas’s peace plan will probably enter the endless collection of peace plans proposed throughout the years of the conflict, which were faded into oblivion. The composition of the current government and the timing of the publication will not give it a chance. Historians will certainly wonder in the future whether a peace plan was ever proposed by an Israeli government. I will give them a hint: not even once.

Prof. Elie Podeh is a Board Member at the Mitvim Institute. He teaches at the Department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.