Op-eds

/ The Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process

Op-eds

/ The Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process

About six months ago, I sat in a coffee shop in al-Tireh, a suburb of Ramallah, and interviewed a senior official within Fatah. The official, wanting to talk about the internal dynamics within the Palestinian leadership, wished to remain anonymous. In between flowery anecdotes about his meetings with Dick Cheney (“He always asked about my family”) the official began to shed some light on the Palestinian UN bid of 2011 and 2012. True to perception, various fault lines and rifts began to emerge between his description of how the UN campaign was formed and how other senior officials had described the process. Was Abbas pressured into the UN? Did close advisors convince him? Did he always have it in the back of his mind? If there was one thing the collective Palestinian narrative could agree on, it was that everyone was convinced their explanation was the only explanation for what would become the largest unilateral policy decision in the post-Oslo years.

In his new book, State of Failure: Yasser Arafat, Mahmoud Abbas, and the Unmaking of the Palestinian State, Jonathan Schanzer attempts to unravel these narratives and provide insight into how the Palestinian leadership navigates the rough seas of pseudostatehood. It’s a daunting task—as Schanzer acknowledges early on, the field is crowded with literature on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet, much of that literature is written in a comparative light; it’s usually the Palestinians in relation to Israel, or in relation to the peace process, or the Arab League, and etc. In putting the internal dynamics of the Palestinian leadership as the focal point, “State of Failure” reveals some truly unsettling facets of how the Palestinians craft and implement their policies. In covering the recent tremors in the political structure, the book focuses on former prime minister Salam Fayyad and his rather inglorious fall from grace in the leadership. The internal disputes, the well-documented rifts and disagreements between Fayyad and the Fatah leadership, all are laid out cogently in the book.

The book isn’t likely to be on the PLO’s reading list anytime soon. And most certainly, if there’s one specific area of the book where Schanzer is likely to reach an impasse with the Palestinian leadership, it’s the description of the UN campaign. In the book, Schanzer takes a contemporary approach, detailing the roots of the campaign in 2005, when Palestinian diplomats began working in earnest with Latin American nations, developing a diplomatic strategy that would eventually lead to 2011. This diplomatic strategy was at times viewed as almost antagonistic to negotiations by some within the leadership, but by 2008 and 2009, when Tzipi Livni had failed to form a negotiation-centric government and Benjamin Netanyahu had ascended instead, the idea of this comprehensive and unilateral diplomatic campaign began to take hold. By 2010, with talks breaking down over settlement moratoriums and varying preconditions, the campaign became the predominant driving force of Palestinian policy. This is where things get murky.

If his approach is a pragmatic analysis of a clear-cut policy evolution, the history being touted by the Palestinian leadership is a little more holistic, a bit more nationalistic, and certainly much more paradigm-driven. In other words, Schanzer’s approach neglects a pre-Oslo history the Palestinian officials are incredibly defensive of. In a report I released this past summer, I interviewed nearly twenty Palestinian officials in search of some clarity on the campaign. Of the myriad narratives that emerged, one thing was clear: the UN campaign was not a recent phenomenon. In the historical waxing and waning of the methods of preference in Palestinian policy, internationalization at the UN has a history that precedes negotiations.

Indeed, Palestinian officials described a process that had roots as far back as the 1970s. One official has even written that the Palestinians first considered the UN track in 1969, at the suggestion of President Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia. By 1974, this track’s foundations were laid in the PLO’s Ten-Point Program, a political manifesto that, among other things, called for Palestinian autonomy of lands “liberated,” and didn’t explicitly rule out other forms of resistance. For a resistance-based liberation movement, the acknowledgment of partial territorial control in Palestine and alternative means of resistance was precedent-setting.

Here, too, is where a historical background would have benefited the book. For even in its brief respite from the fore of Palestinian policy, the UN campaign was never far. Indeed, in 1999, as the end of the 5-year interim Oslo period neared, Yasser Arafat dispatched two deputies, Nabil Sha’ath and Saeb Erekat, to Europe in order to begin gauging support for a unilateral declaration of statehood at the UN. The US promptly countered this campaign, and pressured the Palestinians back to the negotiating table. At the time, President Clinton had managed to dissuade Arafat through several key areas: first, leveraging the well-known fact that a Palestinian unilateral action outside of the Oslo framework would threaten the peace camp in the upcoming Israeli elections, and second, that the US would be willing to host further negotiations if Arafat held off. After a frenetic diplomatic campaign, the US was able to stave off the Palestinian action and set the stage for the Camp David negotiations.

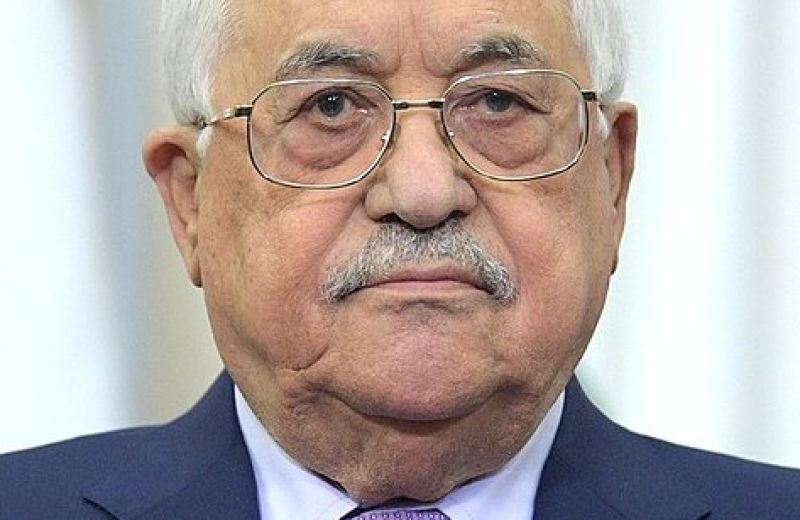

Where does that leave the UN bid in the grand scheme of things now? The Palestinians have halted their campaign in lieu of recent negotiations, a compromise they made with John Kerry in order for talks to be restarted. Should the talks break down, however, or fail to yield an interim agreement by March, the Palestinians can be expected to again gear up for engagement at the international body this coming year. Their engagement, and specifically which entities to engage and to what degree, will be known only to the man at the top, Abbas.

Such is the clouded area of tasseography in the Palestinian Territories that State of Failure deftly interprets. Schanzer discards the rhetoric and nationalist storylines in lieu of the pragmatic, describing the recent leadership’s myopic nature in zero-sum terms. His prognosis is clear: the Palestinian leadership is struggling on two fronts: in negotiating a state’s existence and governing a state entity. In order to do the former, it must improve on the latter. It is not likely to win him many friends in the West Bank. But it is, however, a workman’s analysis of how Palestinian officials form policy and govern in one of the longest and most intractable conflicts of the modern era.