Op-eds

/ Strengthening Israel's Foreign Policy

Op-eds

/ Strengthening Israel's Foreign Policy

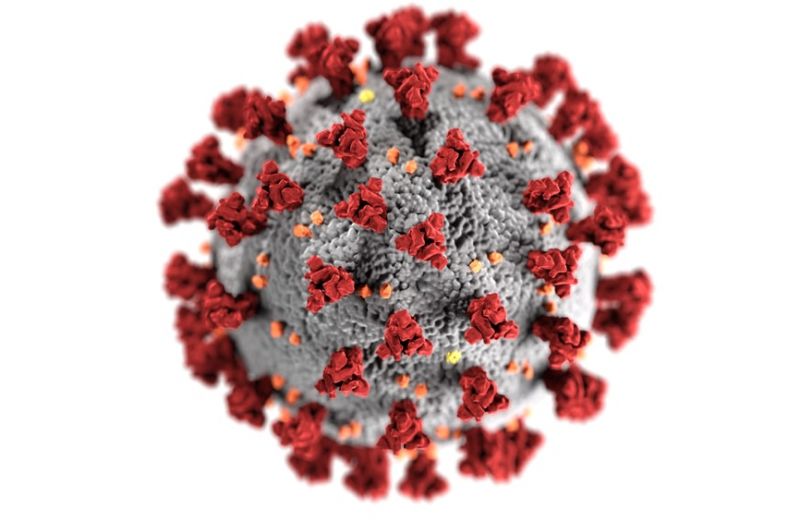

Like so much else, official diplomacy has shifted to virtual communications since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is an opportunity for Israeli diplomacy to lead a new type of diplomatic communication and adapt diplomacy to an era in which relations must be forged without “physical” meetings with representatives of other states.

The Covid-19 pandemic has placed Israeli diplomats on the nation’s frontlines, particularly in helping obtain medical equipment and bringing home Israelis stranded abroad. Although the Foreign Ministry has had to withstand the erosion of its authority and budget, efforts to undermine it and the deterioration of its staff’s working conditions in recent years, Israeli diplomats have been operating relentlessly to accomplish their assigned tasks, with some even contracting the disease.

The pandemic has challenged the core of the diplomatic profession. Diplomatic activity entails forging and developing ties with key economic, social and political figures in foreign states; the professional-personal relationships with those key figures is a crucial element in achieving the tasks assigned by Jerusalem. For instance, such relationships made it possible to fly an experimental drug from Japan to treat Covid-19 patients in Israel, helped bring home Israeli travelers stranded in Peru, and freed a shipment of facemasks held up at an airport in Turkey.

The social distancing induced by the pandemic hampers Israeli diplomats’ ability to conduct the face-to-face meetings traditionally used to develop connections with foreign representatives. Within a very short period, all interpersonal communications have shifted to technology-mediated interaction. Whereas digital platforms served as a supplementary and targeted means in the diplomats’ toolbox in the pre-coronavirus era, at least in the short term, a sharp shift to digital-virtual diplomacy has been necessary. At present, diplomacy is only possible through technologically enabled means of communications. Reliance on digital-virtual platforms should not be perceived as a problem, but rather as an opportunity. The Foreign Ministry should take advantage of the Israeli spirit of entrepreneurship and Israeli technological pre-eminence to invent and lead new diplomatic communications, firstly for Israel’s Foreign Service and subsequently as an example to other diplomats around the world. Efficient implementation of this new form of diplomacy involves three key aspects.

First, planning communications with representatives in a foreign country must include all forms of communications: e-mail, social media platforms and video conferencing. Each suits a different part of the job and different type of relationship-building. For example, to initiate contact and send out feelers regarding shared values and interests, e-mail is preferable as it allows open-ended questions and ambivalent formulation (to the extent necessary). In order to conduct a conversation on sensitive or controversial issues, chat over a digital platform is preferable, because it makes saying “no” easier and the delayed response provides time to consult or find arguments and references to buttress the answer. The World Health Organization (WHO) provided an excellent example of why discussion of sensitive issues should be avoided on video conference when its representative simply hung up on a journalist who asked him about the role of Taiwan in confronting the pandemic. Video calls are best for strengthening personal ties, signaling empathy and reaching agreements, making them a unique form of communication in terms of content and significance. They have in fact become the “physical” meetings between diplomats in the coronavirus era.

Second, complete technological mastery in operating these tools and virtual platforms is a must. That includes simple tasks such as positioning cameras at the correct angle during a video call and silencing microphones when needed. Applications must be used correctly and technical mishaps, such as Boris Johnson’s inadvertent exposure of the dial-in code for the British cabinet’s Zoom meeting, must be avoided. Suddenly, diplomats have not only to control the tilt of their head or the perfect way to tie a bowtie. They must speedily learn the correct use of various technological tools.

Third, professionalism must be acquired in the intricacies of digital and virtual language. In this context, diplomats will have to learn how nuances and cross-cultural codes come across on digital media, such as WhatsApp or a video call, as opposed to during a face-to-face encounter. Should diplomats now employ emojis or GIFs in place of a smile and a slap on the back? On a video call, the choice will be between formal attire, replete with the Foreign Ministry logo and Israeli flag as a backdrop, and informal attire with family photos hanging on the walls, to emphasize common denominators and add a personal dimension to the interaction.

One of the major challenges posed by digital-virtual communications is information security, especially when the subject of the conversation is of a sensitive political or diplomatic nature. This challenge must be addressed in two ways: use of advanced technologies and information security tools, and mutual commitment to avoid revealing the contents of the discussion. Success in maintaining secrecy in a digital-virtual environment will likely raise the level of trust and as a result improve cooperation between the sides.

It is important to note that although a significant part of diplomatic communications will be digital-virtual from now on, this will not replace a diplomatic presence on the ground. Even in the current crisis, Israeli diplomats were required to show up physically at airports to ensure they accomplished their tasks, despite the danger involved. Diplomats’ presence at foreign posts will remain highly significant. Physical proximity enables first-hand comprehension of the climate, culture and reality that cannot be easily reflected in online research or big data tools. While digital-virtual communication will assist diplomacy and retain its newfound importance even once the pandemic is controlled, even now it is no alternative to a physical presence.

Just as companies, schools and universities have shifted to managing tasks and telelearning, once the new diplomacy is implemented, we may find that it yields faster, more precise and efficient results. We may even see negotiation processes and mobilization of political support in international institutions yielding better results when significant use is made of digital-virtual tools. Civil society organizations promoting dialogue between parties to a conflict have already achieved success in recent years through the use of new technologies to build trust and understanding. Now it is the turn of the official representatives to learn from them and bridge gaps. The coronavirus crisis is shaking up political and economic systems and its impact will be evident for a long time to come. Diplomacy is challenged by social distancing rules and diplomats are being forced to adapt to the new world, in an era in which foreign ministries are also challenged to adapt their activities to the rules of modern diplomacy. With the growing dominance of politicians as well as non-state actors in foreign relations, foreign ministries the world over are striving to justify their existence, redefine their mission and fight for relevance in decision-making processes. Diplomats must study the advantages and drawbacks of various technological tools and immediately adopt new and varied means of communications so they can continue carrying out their tasks.

For years, Israeli diplomacy marketed Israeli technological innovation and entrepreneurship to bolster Israel’s image abroad. In recent years, Israel has also demonstrated achievements in digital diplomacy, especially in creating new discourse channels with the citizens of Arab states.

The coronavirus pandemic offers Israeli diplomacy an opportunity to take another step forward and show that it can lead deep and significant change in forging innovative processes of communications to help it successfully implement Israeli foreign policy.